The Wheat Stele Chronicles: An Underwater Artistic Odyssey with Gola Hundun,”Stele del Grano”

An Interview With the Artist Who Installs Underwater

It’s Christmas time – do you have your underwater tree up yet?

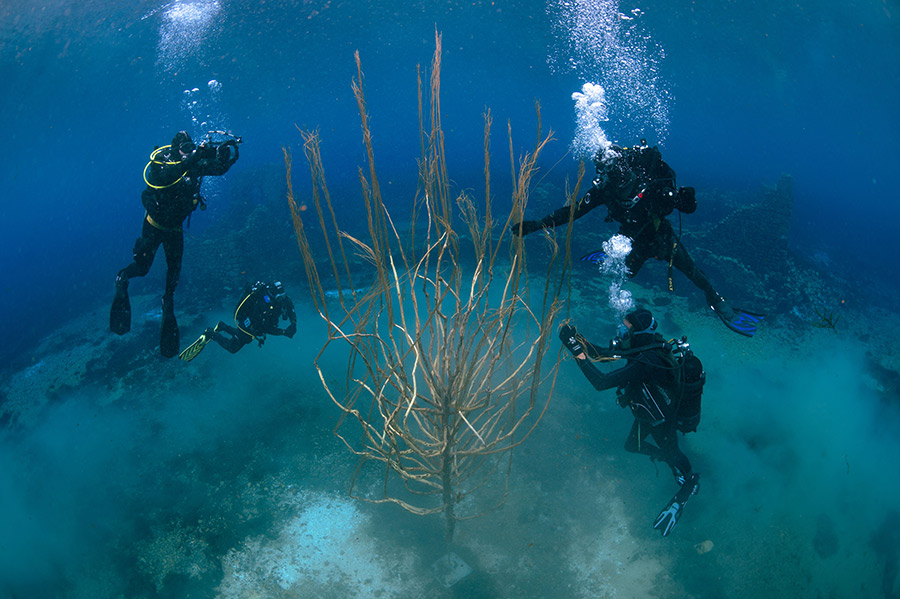

It’s not a Christmas tree that land artist /underwater nature artist Gola Hundun puts up in these photos and video. It looks strikingly alien in this crystal clear new home, but he is jubilant nonetheless. Beneath the tranquil surface of Capodacqua Lake in Capestrano, Italy, his remarkable fusion of art and nature unfolds.

“Stele del Grano,” looks like a visionary underwater installation by an innovative land artist, transforming the submerged ruins of a mill into a canvas for an ethereal narrative. This project, a harmonious blend of history and imagination, offers a unique lens through which to view the ever-evolving relationship between human activity and the natural world.

Concept and Inspiration

“Stele del Grano” is more than an art installation, says Gola; it visually explores the Tirino Valley’s terramorphic history. The artist chose grain as the central motif, a symbol deeply rooted in the valley’s transformation from a wooded haven to a granary of the Papal States. The project weaves a tale of nature’s resilience and human impact, from the Bronze Age settlements to the modern-day artificial reservoir, echoing the mythic stories of lost civilizations like Atlantis.

The Artistic Process and Installation

The physical manifestation of the “Stele del Grano” is crafted from branches and ropes to create a structure that mimics an ear of wheat that has morphed into an anemone-like water plant. It’s a deliberate juxtaposition, an alien yet mimetic presence amid the mill ruins and submerged trees. The installation required the synchronized efforts of numerous divers and assistants, who meticulously worked underwater to anchor this symbolic representation of change and continuity.

A part of the artist’s larger “Habitat” project, an ongoing exploration since 2018, the installation “Habitat” delves into structures built for human needs, now reclaimed by nature. This project contemplates spaces that, though altered, continue to serve as homes for diverse life forms. “Stele del Grano,” in its underwater realm, becomes a visual dialogue about the Anthropocene era, raising questions about the human footprint and nature’s adaptability.

Artistic Vision and Aspirations

The artist’s intention with “Stele del Grano” goes beyond mere visual impact. It’s an invitation to reflect on the dynamic and sometimes tumultuous relationship between human actions and nature’s responses. Through this underwater installation, the artist hopes to inspire viewers to contemplate the coexistence of human and natural worlds, imagining a future where balance and respect define our interactions with the environment.

While “Stele del Grano” may seem a world away from the vibrant immediacy of street art, its core resonates with similar themes of expression, freedom, and environmental commentary. Just as street art captures the pulse of urban landscapes, this underwater installation encapsulates the essence of a natural yet human-influenced environment. It’s bold: an act of free will and art-making that speaks to the enduring power of artistic expression – and its ability to ignite conversation and evoke some sense of wonder.

BSA: We always say that “nature will take over” again. We’ve actually seen this happen during our lifetime when man-made catastrophes occur, such as the Chernobyl explosion in Ukraine and most recently, during the lockdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In both cases, human presence outdoors ceased, and wildlife took over. Plants and animals reclaimed what was once theirs. Tell us more about your interest in this subject. How did you become so immersed in abandoned man-made structures and their inextricable relationship with nature, and what makes you feel so connected with the past, with history?

GH: Let’s say that for me, more than a connection to history, these places propose a future vision that fascinates me, a near future in which man no longer exists but survives through his vestiges and constructs scattered over the territory that has in the meantime assumed a new hybrid form that mixed the rational line with the forms of generative chaos of non-human nature. I consider these abandoned ruins reclaimed by nature as true Temples of Rebirth.

These places in my view are always shrouded in a great romantic fascination and have a disturbing effect on my psyche, on the one hand they tease a hoped-for revenge of the rest of nature on the anthropocene on the other they stage the smashing of our species generating a short-circuit in my anti-speciesist but human brain. My interest in this kind of place was born in me at the end of the last decade. In 2018 I began the first experiments by making ephemeral gold-colored interventions inside the investigated ruins as Ready-Mades and already perfect. Still, through the gold (symbol of sacred nature), I allowed myself to emphasize the inherent creative process. Following several actions, the research took the name of Abitare first and later Habitat.

Habitat Project is conceived as an ethological and metaphysical research about buildings originally built for human needs, neglected and eventually recolonized by new living beings (plants, animals, fungus, lichens) that may convert space and shape but not the concept of space to inhabit.

Neglected buildings all over the world need to be converted or rather demolished.

Most of the time, these operations take time and money. As a result, Nature gradually reclaims what it used to own so that its space becomes populated by different living beings.

Habitat goals are the investigation and study of this phenomenon, seen as a natural artistic process, aiming to show up a new life vision into the anthropic space by the end of the Anthropocene Era.

Its research starts from a visual analysis, develops through artistic intervention, and keeps on with the spontaneous birth of new flora and fauna through time.

BSA: What lessons have you learned from closely observing this relationship?

GH: Nature is everything. Even on those ruins, nature is a struggle, cooperation, it is dualism it is multiple vision, it has no borders, it has no private property, it is generated by multiple physical and consciousness levels one within the other. And if even before Scala Naturae was written much of humanity was already convinced that it was on a higher plane of existence and separate from the rest of living forms, natural reality admits of no objection the human being is part of nature so it can be said absurdly that the concrete walls it builds, are nature, although I myself would tend to say otherwise. .. one can say that plastic is also a part of nature, because it comes from petroleum i.e. microorganisms putrefied billions of years ago, and that is perhaps why other microorganisms today have adapted to eat it. Obviously these statements are provocations of a simplistic flavor the balance of nature in the form we know it is something very fragile. The very definition of nature is something controversial, quoting Norberto Bobbio: “Unfortunately, Nature is one of the most ambiguous terms one is given to come across in the history of philosophy.”

What I want to say is that what I have realized with this research is that the point is not to try to define what is natural and what is artifact but to understand as a species that we have to start immediately to act feeling ourselves as part of nature and stop consuming virgin soil to abandon it cemented made sterile, mono functional, mono cultivated, stop acting as if we were on an inanimate planet, alone, where the rest of the form is a mere material at our disposal. Time, rhythm, perhaps these are elements that really make us diverge from the natural order, our internal time is no longer similar to that of nature but that of the productive logic of Industry and the machine, to that of capitalism.Acting taking into consideration that everything is connected, as was done in ancestral cultures around the world, our main problem is Capitalism.

BSA: For this last project, you went underwater. What surprised you from the experience?

GH: What fascinated me most was the opportunity to learn about and study the upheavals suffered by the area where the lake now stands throughout history.

The contraposition between anthropic action and the action of the other nature have determined a history of incisive transformative movements, resulting in metamorphic peaks of great amplitude that have distorted the form and substance of Capodacqua on several occasions. For this reason, the structure made of branches and ropes that establishes an underwater dialogue with the mill ruins stems from the idea of an ear of wheat that has become something else, a sort of anemone/water plant, precisely to speak of the changing identity of that place. An alien element to the underwater landscape but at the same time mimetic in that it dialogues with other trees trapped under the water, dating back to the period before the dam.

Grain is chosen as the narrative element and guiding thread of the metamorphosis of the area. In fact, while in ancient times the place examined was a wooded valley in which a spring gushed from the underground basin of the Gran Sasso and from there flowed into the Tirino river across the valley, during the Bronze Age the area was already populated by small rural communities and at the source of the river a village arose that contributed to the foundation of Capestrano in Roman times.

Thus began the agricultural colonisation of the area; as we know, gramineae are among the first plants domesticated by mankind and even then they were the main crops. In the Middle Ages, the area was converted into a granary for the Papal States, thus becoming a sort of wheat monoculture; the mills dating from around 1100 AD, now sunk to the bottom of the lake, bear witness to this historical phase, but at that time they exploited the course of the river to grind the wheat from the surrounding fields.

In 1965, a dam was built to interrupt the natural course of the stream with the main purpose of generating an artificial reservoir to irrigate the wheat fields. On that occasion, the mills were submerged in the water, thus generating a unique natural/anthropic hybrid landscape that leaves one fantasizing about the myth of Atlantis, of course to have the opportunity to dive in such place mesmerised me compleatly.

After centuries of human exploitation, nature regained possession of the area, which became an important resting place for the routes of migratory avifauna and a habitat for various types of lake and underwater plants, as well as for the many amphitopes.

BSA: In the video we see beautiful flora on the bed of the lake, but surprisingly few fish. We were also surprised by how clear the water was. Do you think that policies put in place saved the lake?

GH: The clarity of the water is guaranteed by the fact that the lake rises near the surfacing of an underground river (Tirino) that flows for kilometers underground from its source located inside Mount Gran Sasso one of the highest elevations in Italy. This spring water gushes very cold and flowing underground maintains a constant year-round temperature of 8 degrees and is filtered by the underground rocks, characteristics that make the lake water so magnificently transparent. In fact, Lake Capodacqua is a popular destination for divers from all over the world also because it contains those suggestive mills. As I mentioned earlier, the lake was generated by Humans although certainly not for zoo-philanthropy but for utilitarian purposes, actually between the 1980s and 1990s a new human incidence will lead to the extinction of the endemic crayfish that colonised the lake caused by overfishing and the dust pouring in from the Gran Sasso tunnel. Another human incidence will be the introduction of brown trouts first and three pikes later, which will cause the decimation of the trouts and harass the avian fauna. Finally, Capestrano municipality will decide to kill the pikes by local fishermen, the last one was killed in 2007. Today, the lake has become an area of Naturalistic Interest and part of the Gran Sasso e Monti della Laga National Park, and wild species are returning hopefully to repopulate the lake.

Gola Hundun’s. Stele del Grano (Wheat Stele) project at Capodacqua Lake in Capestrano, Italy is part of HABITAT the artist’s ongoing series about human-made structures, architecture, and their relationship with nature and space. Click HERE, HERE, HERE, HERE, HERE, AND HERE to learn more about HABITAT.

Other Articles You May Like from BSA: