Exploring the Emotional Depths of Tracey Emin’s Artwork

# Tracey Emin’s *I Followed You to the End* at White Cube: A Profound Exploration of Life, Death, and Art

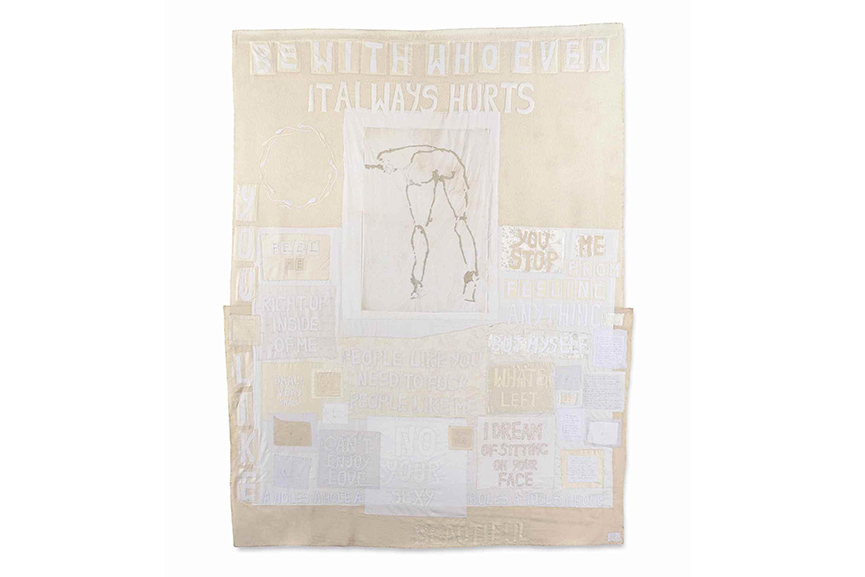

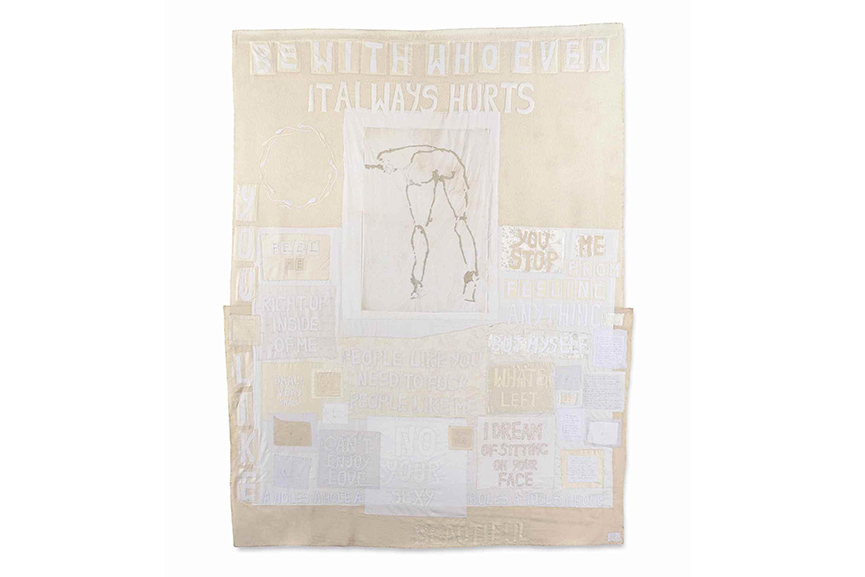

LONDON — Tracey Emin’s latest exhibition at White Cube, *I Followed You to the End*, feels like a continuation and amplification of her 2019 show, *A Fortnight of Tears*. Five years ago, she wrestled with the grief of losing her mother, and now, with her 2024 exhibit, Emin confronts her experiences of another life-altering event: a dire brush with death. Diagnosed with advanced bladder cancer in 2020, Emin underwent harrowing medical treatments, including major surgery, and six months of recovery. Emerging from this ordeal, the show reverberates with an urgency and intimacy that signals a shift in the artist’s journey.

At 61, Emin continues to delve deep into a personal, emotional landscape she has mined since art school in the 1990s. However, there’s a maturity here, a grit sharpened by survival. As Emin herself stated in 2023, *“When you’ve been seriously ill and you come out the other side, you really don’t fuck around anymore, ever.”* Art, for Emin, is no longer just a calling — it has become a necessity, a way to grasp onto life as she faces its fragility.

## The Weight of Mortality

Emin’s work has always been intensely autobiographical, marked by pain, vulnerability, and a raw type of femininity. But *I Followed You to the End* feels particularly urgent. The exhibition comprises 40 paintings and two large bronze sculptures, all completed in 2024, and spans multiple rooms of White Cube’s Bermondsey location. While her 2019 show included an expansive installation of photographic self-portraits wrestling with insomnia, this new exhibit abandons any performative or superficial veneer.

The works are profoundly personal, stemming from Emin’s encounters with illness, survival, and her existential reflections. Intentionally stripped of theatricality, the human figures in her paintings float, writhe, and sit in quiet poses. The starkness of their shapes and the minimalism of the palette draw viewers into an eerie intimacy — through strokes of blue, black, white, and red, Emin finds the balance between what is seen and what is deeply felt.

## The Opening Act: Small Paintings of Isolation

Upon entering the exhibition, visitors are greeted by a narrow hallway lined with small acrylic paintings. Most depict Emin in bed — sometimes alone, sometimes with another figure, and often in the company of a cat. The beds signify not just a place of rest but of contemplation, illness, love, and loss. These small paintings are preludes, warming up to the more expansive emotional canvases that lie ahead.

One can’t help but notice the influence of Emin’s quintessential 1998 installation *My Bed*, where a disheveled bed represented remnants of everyday life, laced with deep emotional turmoil. Here, the bed remains a symbol but now embodies introspection, solitude, and survival.

## The Paintings: Insights from Sleepless Nights

Emin’s larger paintings, which dominate the next rooms, often reflect horizontal perspectives: bodies sprawled, curled, or reclining. This position between wakefulness and sleep becomes both literal and metaphorical in her art. The emotional complexity of transition — from sleep to consciousness, life to death, connection to isolation — is made palpable in these works.

*“More Love Than I Can Remember”* exposes a naked figure on a bed, rendered in fragile, thin blue strokes. Beside the figure sits a cat, watching over her unceremonious posture. The dribbles of paint pull the viewer’s gaze downward, reflecting how time slips in the quiet hours of the night. The work captures a desire for human connection intertwined with a recognition of despair over its fleeting or broken nature.

In *“I Wanted Love”*, a softer palette of pinks and whites offers a respite from the darker emotional landscape. But the transition to one of her most striking works, *“The End of Love”*, is jarring. Here, a figure is shown buried beneath blankets, shrouded in swathes of blood reds and bruised blues. The cat, once again nearby, promises an uncertain tomorrow.

## Verticality and Martyrdom: A Shift in Emotional Orientation

Emin’s inclusion of vertical paintings adds a layer of spiritual ambivalence. In *“I Did Nothing Wrong”*, Emin portrays a woman on her knees, head bowed, with a halo behind her, invoking the imagery of a martyr. It’s not clear whether she is asking for forgiveness or making a statement of resilience. A haunting diptych titled *“My Dead Body – A Trace of Life”* juxtaposes words and imagery: one side blank except for the emotionally charged phrase, *“I