“Examining the Lack of Racial Discussions in Fairy Tales”

**Race and the Evolution of European Fairy Tales: A Closer Look at *Specters of the Marvelous***

Fairy tales, often thought of as timeless narratives of wonder and magic, are shaped by the socio-political and cultural forces of their time. Kimberly J. Lau’s groundbreaking book, *Specters of the Marvelous: Race and the Development of the European Fairy Tale* (2024), challenges this notion by uncovering the racial undercurrents embedded in these classic stories. Lau’s work not only enhances our understanding of the genre’s development but also opens up new avenues for examining the intertwined histories of race, literature, and culture.

### The Central Argument: Race as a Core Element in Fairy Tales

Traditionally, the study of European fairy tales has centered Whiteness, inadvertently erasing the complex racial dynamics that informed the creation and evolution of these narratives. Lau’s book identifies race as an integral component in canonical collections of fairy tales, including Giambattista Basile’s *The Tale of Tales* (Italy, 1634–36), Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy’s *Fairy Tales* (France, 1697), the Grimm Brothers’ *Children and Household Tales* (Germany, 1812–1857), and Andrew and Nora Lang’s *Colored Fairy Books* (Great Britain, 1812–1857). Lau argues that far from being mere reflections of universal human experiences, these texts were, in fact, deeply rooted in the racial and cultural hierarchies of their times.

“From the beginning,” Lau asserts, “the worlds of these fairy tales were always centered around race.” Whiteness, she points out, dominates the genre not as an incidental feature but as a deliberate design, casting people of color as “other.” For instance, in Basile’s *The Tale of Tales*, the name “Lucia” — commonly assigned to enslaved females in premodern Italy — characterizes one of the more sinister roles in his stories. Such insidious racial coding underscores how race has informed the moral and social frameworks of fairy tales across Europe.

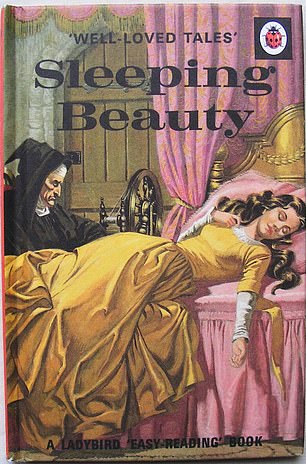

### The Role of Race in Visual and Narrative Adaptations

Beyond the textual narratives, Lau examines how race manifests in the visual interpretations, adaptations, and performances of these tales. Over time, racial markers have been amplified or altered to suit prevailing social attitudes. For example, Wilhelm Grimm’s revisions of “The Jew in the Thornbush” became increasingly antisemitic across successive editions, culminating in grotesque stereotypes by the mid-19th century.

Lau also explores how imperial and missionary expansions subtly infiltrated fairy tale collections. The Langs’ *Colored Fairy Books* reflect an evolving integration of non-European tales, initially limited to those of “civilized” China but later expanded through stories from Indigenous Australian, Bantu, and Armenian traditions. Lau argues that this selective inclusion not only exoticized these cultures but also justified European colonial and imperialist ideologies.

### Universalization as a Tool of Empire

One of *Specters*’ most compelling insights is its critique of the universalization of European fairy tales. By assimilating stories from non-European cultures while reframing them through a Eurocentric lens, these tales effectively mirrored the empire-building strategies of their creators. As Lau notes, this imaginative colonization worked to sustain systems of power, casting European cultural norms as universal truths while marginalizing those outside the fold.

The inclusion of racially diverse stories into European collections was often framed as a celebration of “universal humanity,” but it masked deeper imperialist agendas. Instead of honoring the distinctiveness of non-European tales, this practice often stripped them of their original cultural contexts, reinterpreting them to fit Western archetypes.

### The Intersection of Race and Gender in Fairy Tales

While the book primarily focuses on race, Lau briefly acknowledges vital intersections with gender. During the 17th century, when tales gained popularity in salons hosted by Parisian women, they operated as an exchange of cultural capital and storytelling. Similarly, Grimm’s “spinning tales,” associated with women’s aspirations for productivity, uniquely tied the act of storytelling to traditional gender roles. The figure of the spinner, prevalent in many tales, reflects women’s labor as well as their constrained social mobility.

Yet, as Lau signals, far more work remains to be done in exploring how space, race, and gender converge in the history of fairy tales. Feminist readings of spinning rooms (*Spinnstuben*), where unmarried women gathered for collaborative crafting and storytelling, could offer new insights into how women subverted or reinforced dominant ideologies through these narratives.

### Decolonizing Fairy Tales: The Core Takeaway

Lau’s book is fundamentally concerned with what it means to decolonize the fairy tale — to reveal its racial foundations and reckon with its historical complicity in perpetuating systems of inequality. As Lau succinctly asserts, “It is impossible to think about the fairy tale