An Examination of Orientalism Through a “Both Sides” Perspective

**Exploring the Legacy of Jean Léon Gérôme and the Power of Orientalist Art: A Critical Perspective**

The exhibition *Seeing Is Believing: The Art and Influence of Gérôme*, currently on display at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha, Qatar, offers an intricate meditation on the controversial Orientalist legacy of French artist Jean Léon Gérôme (1824–1904). While the show seeks to dismantle the stereotypes entrenched in Gérôme’s works, it also invites viewers to engage with both the artistic brilliance and the deeply problematic narratives shaping his oeuvre. Curated by Emily Weeks, Giles Hudson, and Sara Raza, the exhibition endeavors to deconstruct the aesthetic and ideological impact of a genre that profoundly influenced Western perceptions of the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia (MENASA).

### Orientalism: Reality, Fantasy, and Everything In Between

The exhibition begins with an introductory framework for understanding Orientalism. As outlined in the opening wall text, Orientalism refers to the ways in which Western artists like Gérôme depicted the MENASA region “often blending reality with fantasy.” Gérôme, who never shied away from using his imagination to embellish or fictionalize the people and landscapes of the “East,” remains a polarizing figure. His works, which range from serene depictions of Islamic architecture to vividly dramatic portrayals of imagined harem life, reflect a fixation with “the exotic” that has been criticized for its complicity in perpetuating imperialist stereotypes.

One of the exhibition’s standout moments is Gérôme’s *Veiled Circassian Lady* (1876), an oil painting that epitomizes the artist’s ability to create photorealistic yet fundamentally misleading representations. While it portrays a beautifully dressed woman nestled in intricate Turkish and Persian textiles, the narrative is misleading; the “Circassian” heroine is not an authentic subject of Gérôme’s travels but rather a studio model in Paris, embodying his European fantasies of Eastern allure.

This process, known as bricolage, underscores Gérôme’s method of collating disparate cultural elements into a unified, yet inaccurate, Oriental tableau. By presenting such works alongside a critical analysis of their artistry and ideological underpinnings, the curators highlight the duality of Gérôme’s legacy: on one hand, a pioneering master of detail and photorealism, and on the other, a purveyor of reductive cultural fantasies.

### Grappling with Gérôme’s Legacy

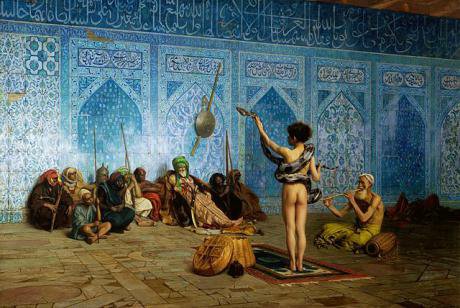

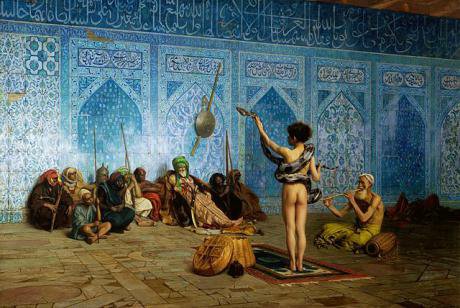

The exhibition does not shy away from Gérôme’s more notorious works, such as *The Slave Market* (1866) or *Snake Charmer* (c. 1879), though their physical absence in the gallery is a deliberate curatorial choice. Instead, viewers are offered a space to reflect on lesser-known works, which, though stunning in execution, continue to distort the “Otherness” of MENASA cultures. Scholars like Edward Said and Linda Nochlin have been pivotal in critiquing the art historical canon Gérôme occupies as one marred by voyeurism, eroticization, and the dehumanization of non-European subjects.

Critically, the exhibition asks a pointed question: Does Gérôme’s technical prowess excuse the moral issues embedded in his gaze? While his work undeniably contributed to Western art’s romantic fascination with the “Orient,” it also reinforced sweeping generalizations that have long deprived MENASA cultures of their complexities.

### The Modern and Contemporary Counter-Gaze

Where *Seeing Is Believing* gains heightened significance is in its second and third sections, which actively challenge the outdated stereotypes propagated by Orientalism. The second section critiques the role of European photography in perpetuating these visual tropes, juxtaposing their dramatized representations with authentic regional depictions from MENASA photographers like Qajar-era Persian ruler Naser al-Din Shah. His candid works reveal a far more nuanced and dignified depiction of Middle Eastern life, starkly contrasting with the European tendency toward excess and spectacle.

The third section transitions into global contemporary art, where Raza’s curatorial intervention offers a resounding counter-narrative to the colonial gaze. Through the works of artists like Nadia Kaabi-Linke and Aziza Shadenova, we encounter artistic expressions that resist voyeurism and reclaim the narrative agency of MENASA subjects. Kaabi-Linke’s installation, *One Olive Garden Tree* (2024), is particularly striking as a metaphorical representation of ongoing colonial occupies. It allows visitors to explore layers of displacement, resilience, and survival, underscoring why contemporary MENASA artists play such an essential role in dismantling Orientalist legacies.

The inclusion of vibrant works by Baya Mahieddine furthers this dialogue. Blending semi-abstract patterns and figures, these contemporary artworks offer audiences a refreshing alternative to European essentialization, grounding their visual language in authenticity and lived experience.

### Is Gérôme Worth Revisiting?

One of the lingering questions in *Seeing Is Believing* is whether Gér