Examining Corruption in the Contemporary Art World: Is It on the Rise?

**Art in the Age of Capitalism: The Crisis of Contemporary Museums**

The relationship between art, wealth, and politics has never been as scrutinized as it is today. In an era where museums and cultural institutions are becoming embroiled in controversies related to funding and questionable ethics, the art world finds itself confronting the darker side of capitalism. Rachel Spence’s new book, *Battle for the Museum: Cultural Institutions in Crisis*, offers a bold critique of the current art ecosystem, where the lines between cultural preservation, commerce, and ethics have blurred beyond recognition.

### The Problem of Context in Political Art

In 2006, art critic Rachel Spence experienced a moment of unsettling cognitive dissonance when she encountered Barbara Kruger’s famous piece “I shop therefore I am” in Venice’s Palazzo Grassi, part of the private Pinault Collection. The artwork, an iconic critique of consumerism, stood in stark contrast to its surroundings—a museum owned by a French billionaire. This paradox lay at the heart of Spence’s realization: within the context of elite capitalist ownership, political art was at risk of being reduced to a hollow echo of its original statement. The skewed dynamics between wealth, culture, and politics that troubled her then have only intensified in the years since.

### The Art Ecosystem Capitalism Created

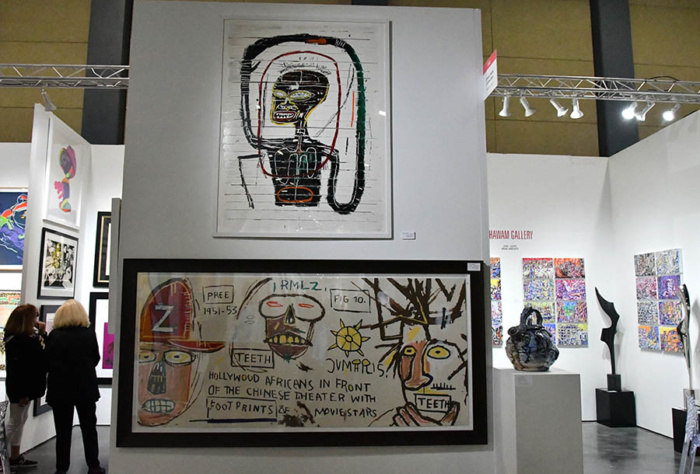

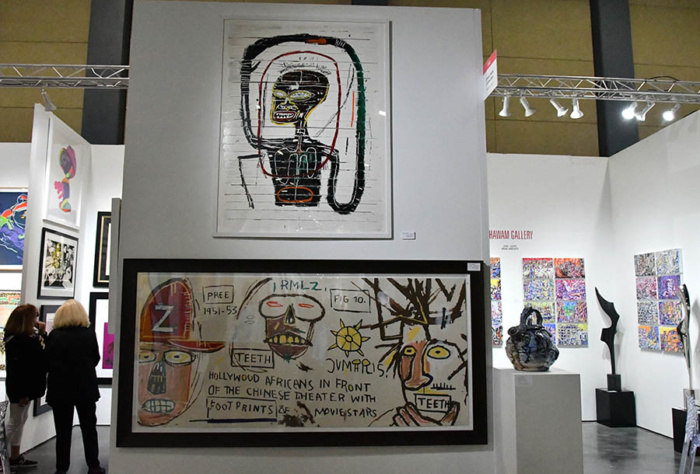

Spence introduces readers to what she terms “Planet Art,” a metaphor for the precarious and contradictory system that makes up today’s art world. She asserts that capitalism, rather than artistic merit or social value, is the dominant force driving cultural institutions—specifically auction houses, museums, galleries, and art fairs—where the primary aim is profit. Her vigorous critique centers on how museums, originally intended to preserve and democratize access to art, have transformed into luxury playgrounds for the mega-rich.

A glaring example of this dynamic is the recent shift toward the commodification of museums. Where they once arguably held a civic and educational function, many museums are evolving into trend-savvy, consumer-driven organizations. Spence highlights how gift shops and cafes have become focal points for financial gain, overshadowing the actual collections they’re meant to protect.

### Controversial Funding and Ethics in Museums

A central controversy Spence unpacks is the problematic funding streams that have allowed museums to thrive in their current capitalist form. In particular, she scrutinizes wealthy and often morally compromised donors. The 2018 protests at the Whitney Museum against board member and munitions manufacturer Warren Kanders are discussed at length. Activists targeted Kanders due to his company’s production of tear gas, demanding his ousting from one of New York’s most prestigious cultural institutions—a demand that eventually led to his resignation.

The controversies don’t stop there. Spence sheds light on other dubious donors, including Leon Black, a financier with ties to Jeffrey Epstein, and the notorious Sackler family, whose name has been removed from several institutions due to their connection to the opioid crisis. Furthermore, Spence critiques the lure of oil money, specifically BP’s sponsorships of UK institutions and Shell’s influence over the National Gallery, which have sparked public outcry and protests among climate activists.

### Museums as Tools for Image Rehabilitation?

One of the most insidious trends Spence explores is how the super-wealthy are using art and museum ownership as a way to sanitize their public reputations. For corrupt, harmful, or exploitative elites, philanthropy in the art world serves as an expensive—but effective—public relations endeavor. By inserting themselves into cultural institutions, these individuals can sidestep scrutiny and position themselves as patrons of the arts.

What this means, according to Spence, is that the art world increasingly prioritizes appeasing the interests of the wealthy rather than serving as a center for social and cultural dialogue. Worse still, the high-level integration of capital and cultural institutions means that art’s political potential—its ability to challenge, disrupt, or represent the marginalized—is neutralized.

### Attempts at Resistance: Activism and Unionization

Despite the overwhelming dominance of capital in the art world, resistance is growing both within and outside these institutions. Spence celebrates recent waves of museum workers unionizing, demanding fair wages and better working conditions. From the [American Folk Art Museum](https://hyperallergic.com/918497/american-folk-art-museum-workers-move-to-unionize/) to the Brooklyn Museum, workers are pushing back against the exploitation perpetuated by these powerful institutions.

Organizations like [Decolonize This Place](https://hyperallergic.com/tag/decolonize-this-place/) are also shaking up the foundations of museums by leading activist efforts to decolonize exhibitions, protest against the questionable ethics of museum trustees, and spotlight systemic injustices in the way cultural institutions operate. The fourth annual Anti-Columbus Day tour in 2019, in which hundreds marched between New York’s American Museum of Natural History and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is just one example of such