Brenda Goodman Depicts Human Struggles Through Her Paintings

**Brenda Goodman: A Journey of Uncompromised Artistic Expression**

Brenda Goodman, now 81, stands as one of the most distinctive voices in contemporary art — a creator whose nearly five-decade-long career defies categorization. Since her first solo exhibition in 1973, Goodman has refused to be confined to any particular style, rendering her body of work a continual exploration of form, narrative, and emotion. Her refusal to conform to the expectations of abstraction or figuration places her outside the normal trajectory that many painters of her generation would follow. Instead, Goodman has forged her own path, producing haunting, psychologically intense works that speak to both personal trauma and universal human experience.

Her latest exhibition, *A Long Journey: Paintings from 1989 to 2024*, currently on view at Pamela Salisbury Gallery in Hudson, New York, offers a panoramic exploration of Goodman’s work from the late 20th century to the present. It’s a testament to her artistic range, encompassing everything from disturbing self-portraits to abstract canvases, all unified by a raw intensity that challenges viewers.

### The Unclassifiable Nature of Goodman’s Art

One of the most striking aspects of Goodman’s oeuvre is how impossible it is to categorize. While many artists develop a “signature style,” Goodman has continually evolved, rejecting the constraints that would limit her artistic inquiry. Her work spans from detailed, often grotesque self-portraits to stark abstraction. For Goodman, painting is less about developing a singular “look” and more about conveying the complex, often disconcerting, emotions bubbling beneath the surface of daily existence.

Goodman’s early self-portraits — some of her most discussed works — are particularly gripping. These large, harrowing depictions of herself are driven by a near-painful psychological intensity. As though channeling Francisco Goya’s macabre “Saturn Devouring His Son” (1820–23), Goodman paints figures possessed by animal-like hunger, gorging on food that may symbolize something far beyond mere sustenance — raw desire, power, or the complexities of identity. But Goodman does not explicitly define what her figures are consuming, opening a space in which her vision of herself as both creator and subject merges with broader, shared human experiences.

Despite the universal themes within these works, major institutions like the Whitney Museum of American Art and MoMA have largely overlooked Goodman. The absence of her work from such prominent collections raises questions. Why would these institutions avoid an artist of this stature? Is it Goodman’s unswerving commitment to emotional ferocity her use of distortion and sheer psychological rawness — characteristics often eschewed in favor of cooler, more detached aesthetics? These are questions worth pondering as New York’s art scene continues to open up to more diverse and radical voices.

### Artistic Life Beyond New York

Detroit has offered Goodman more recognition than New York ever did. In 2015, a major retrospective at the College for Creative Studies in Detroit gave the public a rare opportunity to see the breadth of her talent. The Detroit show included works from the early 1960s, revealing the extent of Goodman’s evolution. Such exhibitions serve to remind audiences of the sheer complexity of Goodman’s art: a journey that traverses figuration, abstraction, and everything in between, often within the same piece.

Goodman’s unwillingness to adopt a commercial style has sometimes left her on the periphery of the hyper-capitalist, trend-driven New York art world. However, it is precisely this refusal to “fit in” that makes Goodman’s work so valuable.

### Confrontational Abstraction and Symbolism: Key Works

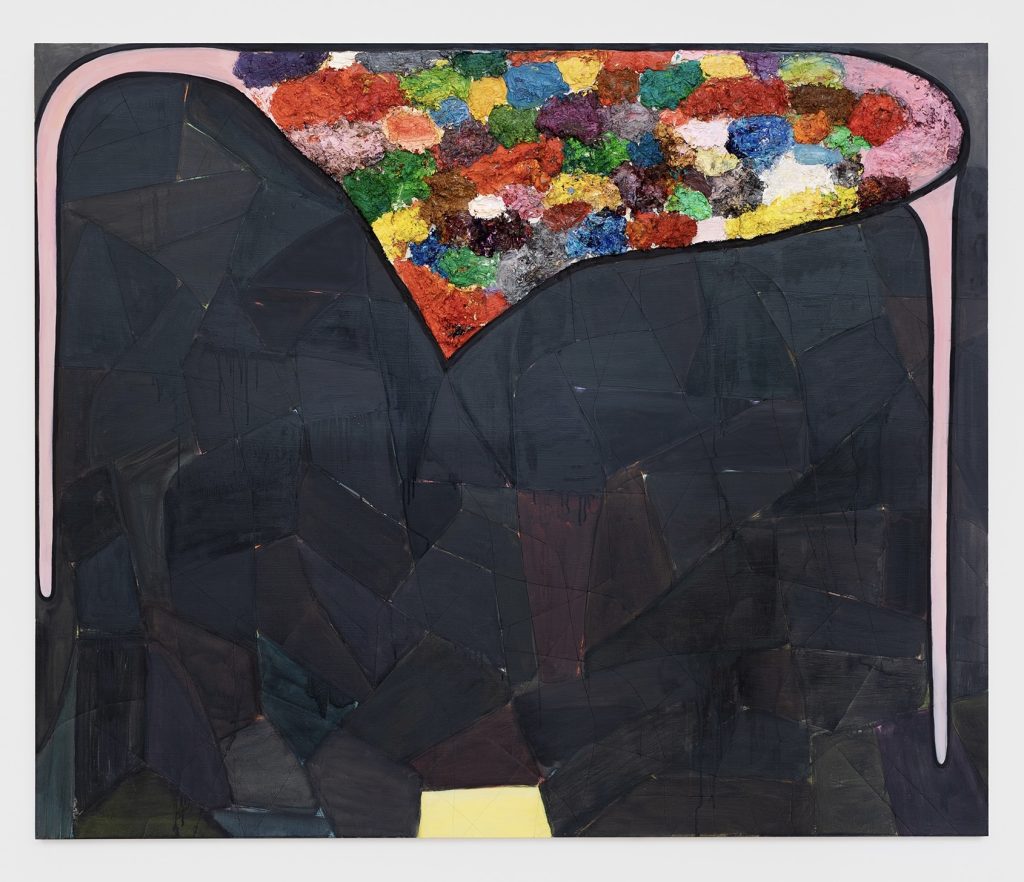

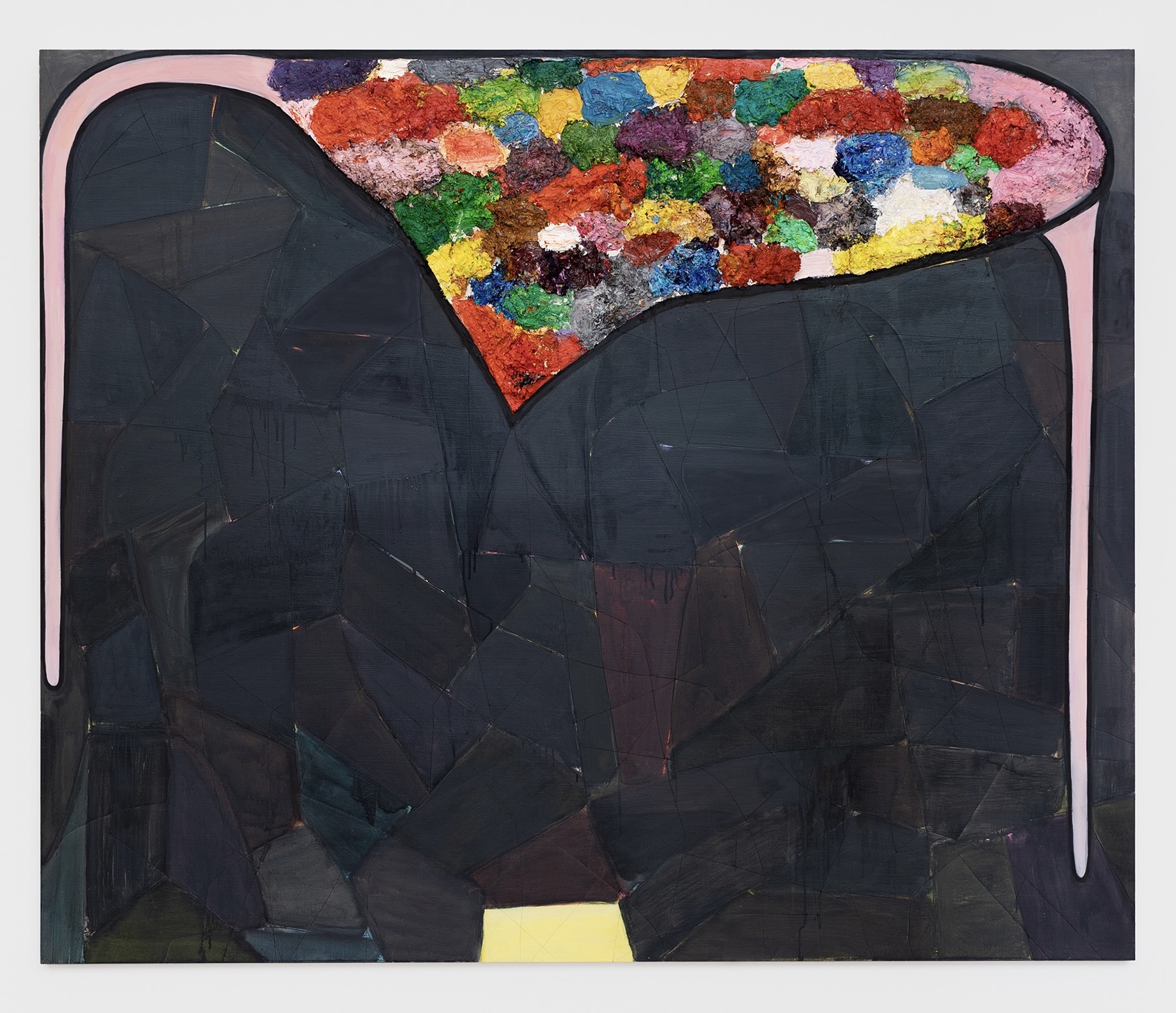

The current exhibition in Hudson includes 21 pieces, which run the gamut from the representational to the abstract, showcasing her enduring ability to merge geometric shapes with biomorphic forms, figuration with abstraction. The results range from works that challenge symbolic interpretation to those that leave viewers entirely unsure of what they’re seeing — but nonetheless gripped by a sense of unease or tension.

Take *Find It – It’s Yours* (2021), one of Goodman’s more abstract works. Dominated by gray and black tones, the canvas is interrupted by irregularly shaped, colorful geometric forms in one corner. Black lines scrawl across the middle section of the painting, seemingly forming a tangled network that contrasts sharply with the incised wood surface underneath. The scarred surface hints at emotional scars, and the interaction between texture and line complicates any smooth reading of the artwork.

Another exceptional piece in the show is *Studio 3* (2023), where Goodman returns to more representational forms. The canvas depicts her studio, yet it’s as much about the emotional undertones as it is a traditional interior scene. A bright painting on an easel, which features a triangular form suggestive of a witch’s hat, is flanked by works in-progress spread across the walls of the studio. Despite the legibility of the items depicted,