“Recognition at Last: Celebrating the Legacy of an Indigenous Modernist Painter”

**Mary Sully: A Hidden Pioneer in Native and Modernist Art Merges Two Worlds**

Through January 2025, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is showcasing *Mary Sully: Native Modern*, a ground-breaking exhibition highlighting the previously unknown yet remarkable Native artist Mary Sully (born as Susan Mabel Deloria). After being obscured in obscurity for almost a century, Sully’s unique voice has finally found light, marking her deserved place in both Native American and Modernist art traditions.

This exhibition, Sully’s first major solo show, consists of 25 of her approximately 200 works, mostly composed of colored pencil on paper, which interlace Native symbolism, modern geometric abstraction, pop culture, and social commentary.

### A Life Lived in Shadows

Mary Sully was born in 1896 on the Standing Rock Reservation, home to Yankton Dakota Sioux, in present-day South Dakota. Her lineage connects her to a distinguished Native family, solidifying her awareness of her indigenous roots in every piece of work. However, Sully spent most of her life in isolation, and her artistic activities were more closely tied to personal compulsions rather than a professional body of work. She was not part of any art movement, unassociated with formal art circles, and never exhibited or sold her work during her lifetime.

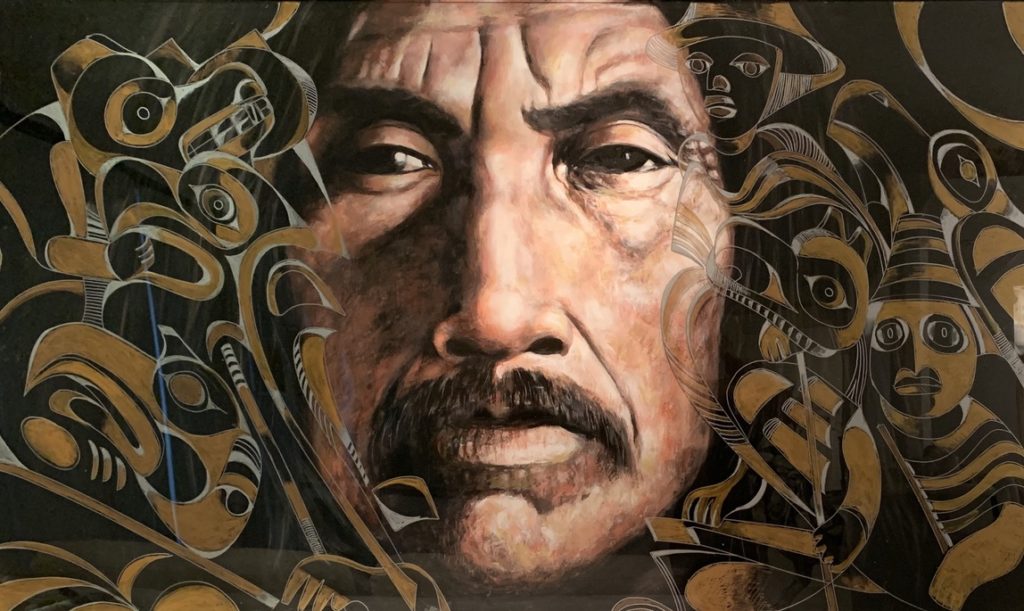

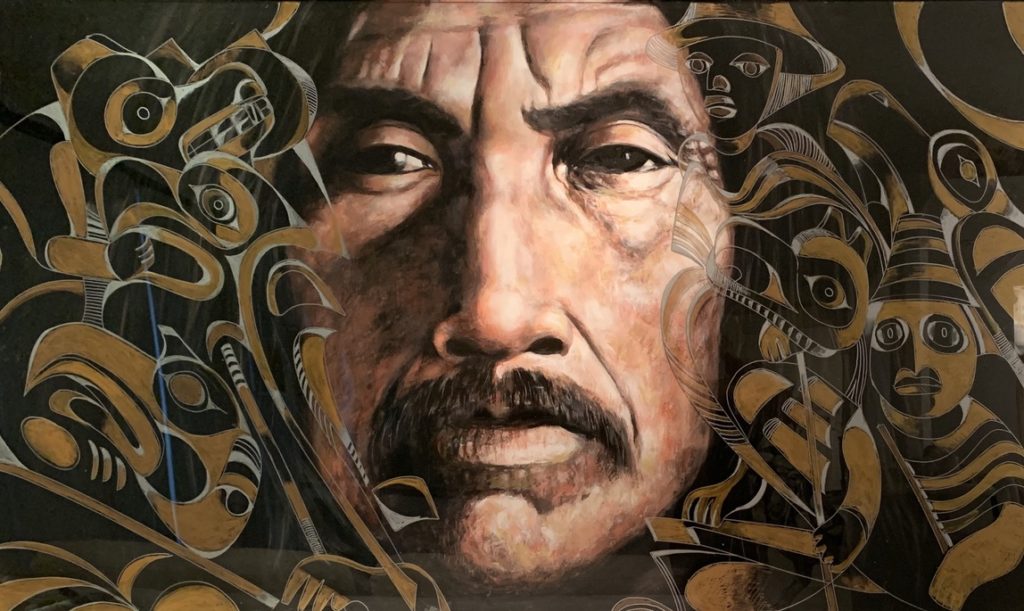

Despite the obscurity and lack of resources, Sully’s art eloquently fuses traditional Native motifs with early 20th-century modernist influences, such as Art Deco and Art Nouveau, to reflect the complexity of her world. Central to her unique voice are layered cultural arguments using abstract forms and spirited maximalism, combined with commentary on figures from American entertainment and political history.

### Sully’s Rediscovery through Family Ties

Sully’s art remained unknown until it caught the attention of her great-nephew, historian Philip J. Deloria, who published a revelatory book in 2019 entitled *Mary Sully: Toward an American Indian Abstract*. Deloria’s exploration into his great-aunt’s life unveiled not just forgotten family history but also a body of artwork that challenges the established conversations surrounding Modernism and Native art. Intrigued by Sully’s ability to exist in multiple cultural and artistic dimensions simultaneously, Deloria’s research led to a resurgence of interest in her work, culminating in this notable exhibition at The Met.

### Exploring the Exhibition

Upon entering the gallery, visitors are met with Sully’s signature “Personality Prints,” intimate, multi-paneled drawings that depict famous 20th-century personalities like Gertrude Stein, Babe Ruth, and Fred Astaire. These pieces are laden with symbolism. Whether showing abstracted footprints evocative of Astaire’s dancing, or blending Ruth’s achievements and geometric patterns, each print mixes a keen observation of pop culture with Native storytelling elements and modern graphic patterns.

Each artwork consists of three distinct vertical panels. The top panel typically symbolizes a famous figure’s key characteristics through vibrant symbols and abstract forms. In the middle panel, the abstract shapes zoom in on specific patterns, offering graphic repetitions akin to Art Deco visuals. The bottom panel is often a homage to Sully’s Native American heritage, featuring motifs from Lakota Sioux beadwork and textile designs, which she had a deep affinity for.

Her unique technique of merging geometric and cultural motifs with American pop culture serves as a captivating counterpoint to conventional Native art, which at the time was often either romanticized or excluded from mainstream museum spaces.

### Layered Cultural Commentary

Sully’s genius lies in the fusion of dual worlds—she was both an interpreter of modern American urban life and a protector of Native traditions. The juxtaposition of symbols, patterns, and cultural references in her work brings forward a dialogue between colonial and Indigenous worlds. This dialogue is crucial given Sully’s historical context, living during times when Native identity was under threat of erasure due to forced assimilation policies in the United States.

Her artistic approach blurs the line between Native art and Modernism, challenging the rigid constructs and misunderstanding of these artistic styles as mutually exclusive. Rather, Sully demonstrates that Native art is dynamic, innovative, and complex, and she employs Modernism’s aesthetic techniques to demonstrate this effort.

### Bridging Forgotten History with Modern Scholarship

At the forefront of this story is the nature of Sully’s rediscovery, especially after decades of obscurity. Before Deloria’s research, her artworks lived in boxes and suitcases, moving between relatives, forgotten after a house fire even threatened to destroy them for good. As a result, her art lived a precarious existence—hidden within the fabric of history, much like how Native voices and stories have often been sidelined in art and academia.

The Met’s inclusion of Sully’s work prominently in both their American Wing exhibitions and larger collections signals a turning point in contemporary awareness and recognition of historically overlooked women artists, particularly Native women. No longer viewed as merely a marginal figure, Mary