Eadweard Muybridge and the Invention of the Motion Picture Technology

The Motion That Changed the World:

Exploring Muybridge and the Dawn of Cinema Through Guy Delisle’s Graphic Biography

Before modern cinema dazzled audiences with blockbusters and digital wizardry, it emerged from a centuries-long quest to capture movement and time — a journey where the boundary between science and art blurred. One of the pivotal figures in this journey was Eadweard Muybridge, a 19th-century photographer whose revolutionary motion studies laid the groundwork for the moving image. In the new graphic novel Muybridge (2025), acclaimed cartoonist Guy Delisle brings to life not only the eccentric personality of Muybridge himself but also the broader tapestry of innovation, controversy, and transformation in which photography evolved into cinema.

A Pioneering Figure in a Transformational Era

Eadweard Muybridge isn’t your average photographic pioneer. Born Edward Muggeridge in Kingston upon Thames, England, he reinvented himself in America, changing his name to reflect Anglo-Saxon heritage and becoming one of the most enigmatic figures of the Gilded Age. Best remembered for settling a bet over whether a galloping horse ever has all four hooves off the ground (it does), Muybridge essentially invented motion photography through his elaborate series of still images, which he later projected using his own creation — the zoopraxiscope.

But Guy Delisle’s graphic novel doesn’t merely recount Muybridge’s technical achievements. It delves into the colorful and, at times, scandalous details of his personal life. These include a traumatic brain injury that some scholars believe affected his temperament, his trial and acquittal for the murder of his wife’s lover (deemed “justifiable homicide”), and his complicated collaborations with powerful figures like Leland Stanford, the robber baron who funded his famous equine studies.

In the hands of Delisle, Muybridge’s life becomes not just a biographical narrative, but a lens through which we view the emergence of a new visual culture.

Bringing History to Life Through Comics

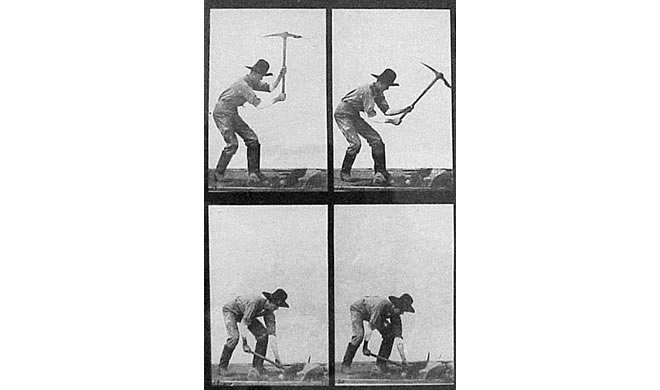

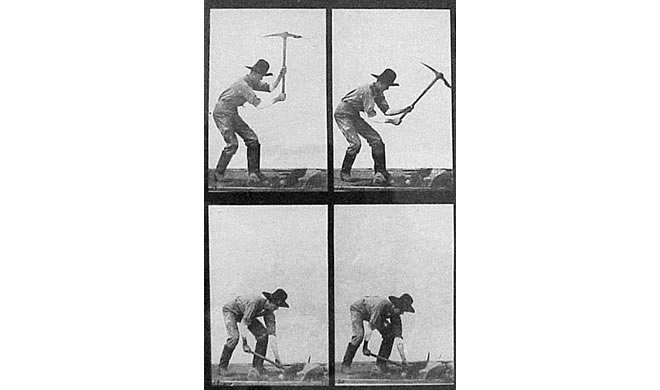

The medium of comics turns out to be uniquely suited to telling Muybridge’s story. While his photographic works are typically associated with cinematic movement, they were originally conceived as sequences of static images — more akin to comic panels than to modern film. In this, Delisle finds harmony between subject and form. He employs the visual language of comics — frames, sequential art, and careful pacing of moments — to mirror the way Muybridge aligned still images to conjure motion.

In key scenes, such as the moment of the infamous murder or Muybridge’s own death, Delisle emulates the aesthetic and rhythm of a motion study, capturing the events in slow, fragmented frames. These panels echo the principle of persistence of vision — the optical illusion that makes cinema possible — while subtly inviting the reader to contemplate how both comics and film manipulate time and sequence to portray action and emotion.

A Broader Historical Canvas

While Muybridge’s life forms the narrative spine, the book also introduces a gallery of contemporary and historical figures who had a hand in early visual technology. Among them: Joseph Plateau, inventor of the phenakistiscope (an early animation device); William Kennedy Dickson, assistant to Thomas Edison and developer of the kinetoscope; and the Lumière brothers, often credited with the first public film screening.

Their cameo appearances expand the scope of the book, framing Muybridge’s inventions within a dynamic landscape of innovation and competition. These intersections remind readers that the advent of cinema was not the achievement of a single genius but rather a mosaic built over time by many visionaries, often borrowing from and outpacing each other.

Delisle also ventures into the changing societal and artistic implications of photography in the 19th century. By including critics like Charles Baudelaire, who feared photography would undermine the world of painting, Delisle shows just how disruptive the photographic medium was to previously established artistic conventions. Photography was no longer just an art; it was fast becoming an industrial and documentary tool that served science, commerce, and empire.

The Contrast of Realism and Abstraction

Delisle’s signature cartoony drawing style contrasts notably with the stark realism of Muybridge’s actual photographic sequences, which are periodically reproduced within the book. This visual tension between the stylized and the photoreal reminds readers of the interpretive nature of human storytelling — even in a world that prides itself on objectivity and realism via the camera lens.

The inclusion of reprinted motion studies — and their juxtaposition with hand-drawn depictions of daily life — underscores a key point: that photography changed not just how we perceive time, but also how we imagine and narrate our reality.

A Masterfully Layered Biography

Muybridge (2025), translated by Rob Aspinall and Helge Dascher and published by Drawn & Quarterly, is part biography, part cultural history, and part playful homage to the visual technologies that shape our world. Although Muy