An Artist Who Redefined the Limits of the Human Body in Art

Title: Exploring the Radical Legacy of Fakir Musafar in A Body to Live In

In the documentary A Body to Live In, director Angelo Madsen crafts a vivid and reflective portrait of Roland Loomis — better known by his alias, Fakir Musafar — a man widely considered the father of the body modification movement. Through a compelling mix of archival imagery, interviews, and artful narration, the documentary delves into Musafar’s unconventional journey from small-town altar boy to a groundbreaking figure in the realms of performance art, sexuality, and spirituality.

A Trial of Flesh and Spirit: The Early Years of Fakir Musafar

Born in 1930, Musafar’s fascination with the limits and symbolism of the human body began at an early age. As a teenager, he transformed his mother’s fruit cellar into a makeshift darkroom where he created self-portraits that showcased early experiments in body modification. These images—showing him bound by ropes, pierced, tattooed, or lying on bed-of-nails altar-like constructions—captured his evolving philosophy: the body as a vessel for transformation.

Raised in a devout Lutheran household, Musafar’s creations defied both social and religious Orthodoxies. His aesthetic drew inspiration from circus performers, “freak shows,” and Indigenous rites of passage—all of which would later fuel the philosophies behind the so-called “Modern Primitive” movement.

Modern Primitivism: Combining Ritual, Pain, and Art

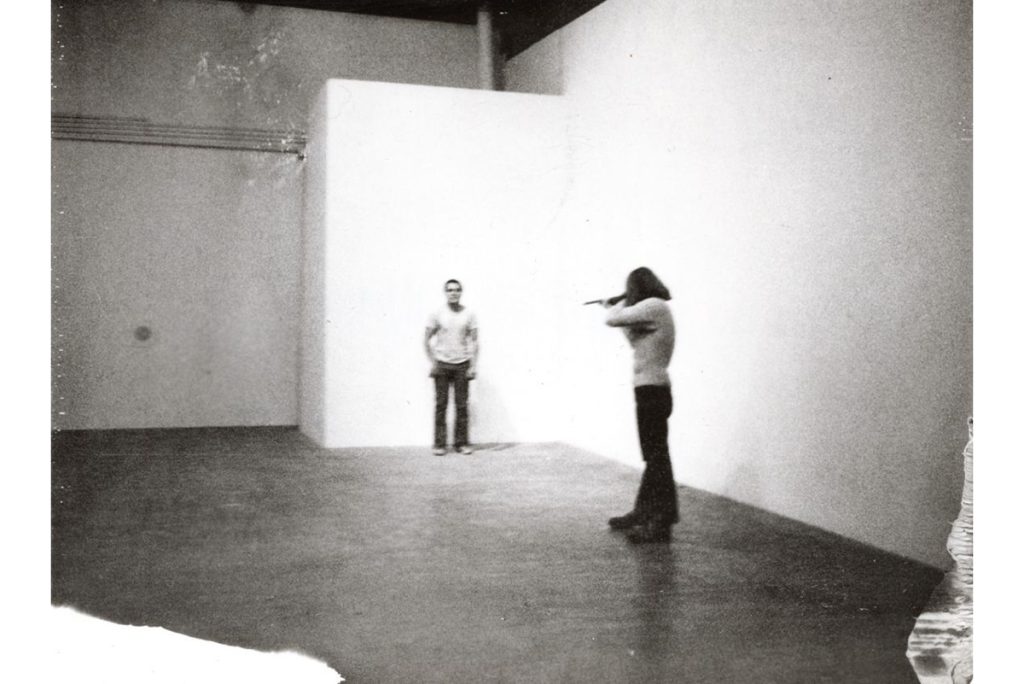

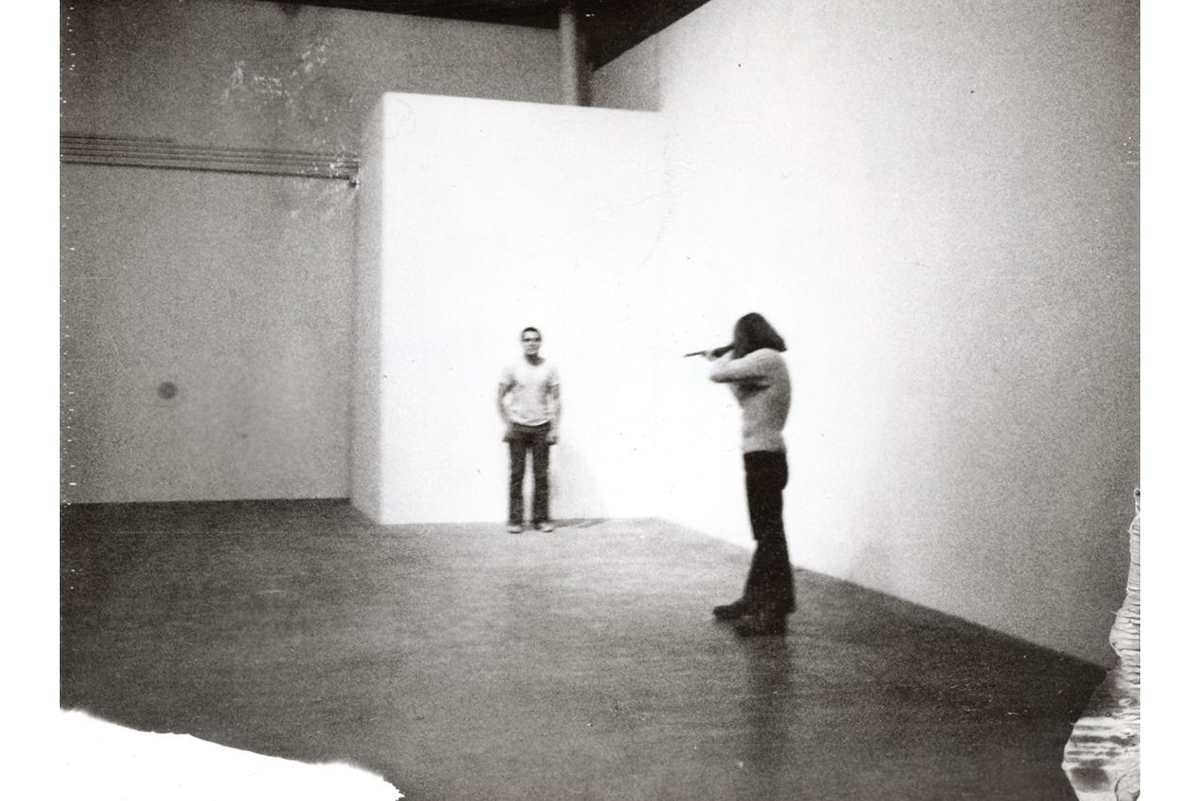

The term “Modern Primitive,” largely popularized in the late 20th century, refers to a cultural trend wherein individuals perform body rituals—such as piercing, branding, suspension, or tattooing—often drawn from Indigenous traditions. These acts were not merely aesthetic for Musafar and his followers; they were transformational experiences designed to forge deeper psychic or spiritual connections.

Musafar articulated this vision through his zine, Piercing Fans International Quarterly, which would evolve into a platform for exploring the artistic and meditative dimensions of pain and body ritual. In footage featured in A Body to Live In, he explains, “When you make an opening in somebody’s body, you’re making an opening in a psychic body.”

A Queer Cultural Moment

A Body to Live In also explores the significant overlap between Musafar’s work and the emergent gay leather and kink cultures of San Francisco in the 1970s and 1980s. As tattoos and piercings gradually became part of mainstream fashion, Musafar pushed beyond aesthetics into deeper, sometimes darker realms—where acts of body modification spoke to personal trauma, collective grief, and spiritual liberation.

His wife and artistic partner, Cléo Dubois, recounts one of the most intense intersections of body art and healing in the film, as she undergoes a clitoral piercing ceremony designed to purge deep-seated trauma from past sexual violence. With drumming, chanting, and group solidarity, the event evolved into a ritual of empowerment.

This sacred-meets-subversive ethos resonated powerfully within queer communities navigating the devastation of the AIDS crisis. For many, body piercing, ritual suspension, and scarification became ways of regaining agency and feeling something—anything—amidst mourning and alienation.

Ethical Entanglements and Cultural Appropriation

Despite its groundbreaking elements, the Modern Primitive movement was not without controversy. A Body to Live In does not shy away from the problematic aspects of Musafar’s legacy, especially in regard to cultural appropriation. As a white man living near the Sissiton Sioux Reservation, Musafar admittedly drew inspiration from Native practices that were not his own.

This borrowing came under increased scrutiny over time, with several Indigenous leaders and tribal councils denouncing the use of sacred rituals by non-natives. As the documentary highlights, a 1986 televised confrontation between Musafar and Indigenous tribal leaders marked a breaking point, and by 2003, tribes like the Lakota formally banned non-Indigenous people from participating in their sacred rites.

A Life Beyond Flesh

Perhaps one of the film’s most moving contributions is its treatment of Musafar’s final years. As he grappled with cancer, Musafar viewed his body not as a deteriorating shell but as an evolving canvas—one that had served its purpose in a life devoted to transmutation. In his final reflections, he declared that the ultimate goal of life was to “finally get out of a physical condition.”

A Body to Live In does not present Musafar as a flawless hero. Instead, it invites viewers to appreciate the complexity of his legacy, offering a nuanced analysis that resists naïve nostalgia or moral panic. The film is equal parts homage, critique, and meditation—an exploration of the aesthetic, spiritual, and cultural tensions at play when the body becomes a site of rebellion, healing, and art.

Conclusion

Fakir Musafar’s contributions to body art and self-expression remain both radical and divisive. A Body to Live In elegantly navigates this terrain,