Reevaluating Paul Gauguin: Assessing His Legacy and Controversies

Reevaluating Paul Gauguin: Art, Myth, and the Morality of the Artist

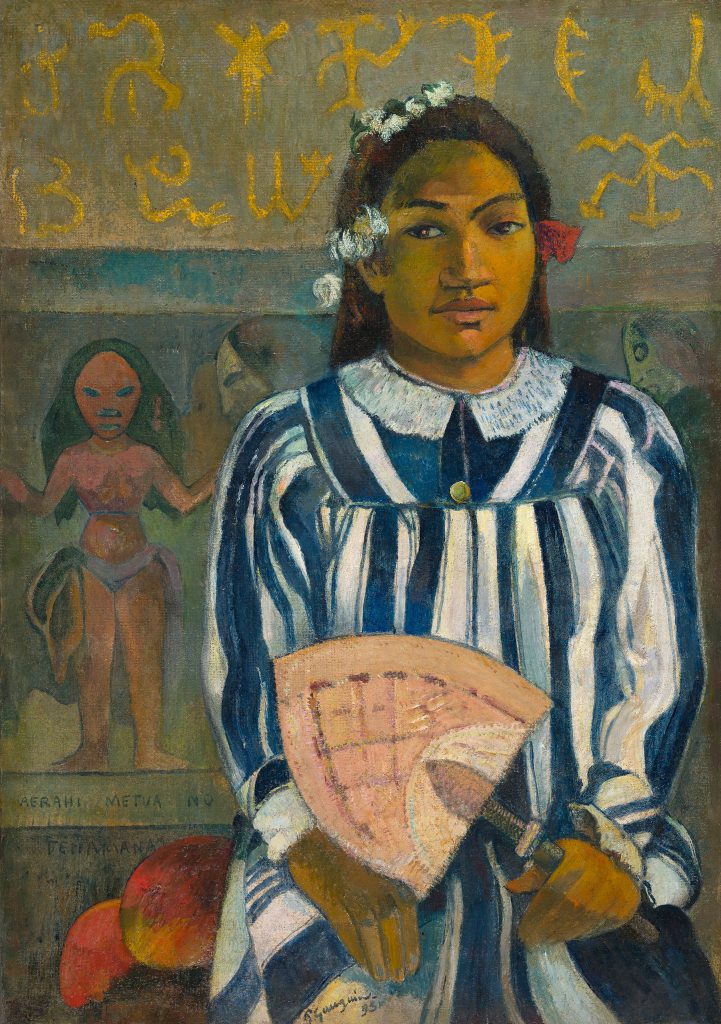

Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) remains one of the most influential — and controversial — figures in the history of modern art. Famed for his vivid color palettes, symbolic representations, and his role in shaping the primitivist movement, Gauguin’s work has long been part of the canonical bedrock of Western art. Yet the mythology surrounding his life, particularly his time in French Polynesia, blurs the line between artistic genius and ethical culpability. In recent years, scholars, critics, and the wider public have wrestled with the question: How do we separate the art from the artist — or should we?

A Complex Legacy

Gauguin’s life exemplifies many of the tensions inherent in Western art history. Born in Paris, he briefly lived in Peru during childhood. His life journey took him from working as a successful stockbroker in France to becoming a struggling, self-mythologizing artist seeking inspiration in Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands. During the late 19th century, Gauguin abandoned his wife and children to pursue a new life, one that he himself romanticized as a return to the “savage” and “uncivilized,” rife with artistic potential and personal liberation.

In this environment, he produced many of his best-known works, including Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897) and Spirit of the Dead Watching (1892). These colorful, symbol-laden paintings challenged European academic traditions and helped shape the Post-Impressionist and Symbolist movements. He became celebrated for introducing exoticized depictions of Polynesian femininity, spirituality, and landscape into Western art.

But beneath these striking images lies a darker truth.

Colonial Fantasies and Realities

Modern critiques have zeroed in on Gauguin’s deeply problematic behavior, particularly his sexual relationships with underage Polynesian girls. Gauguin “married” several girls as young as 13 while in his 40s and 50s. He allegedly exposed them to syphilis (although the latest forensic analysis on his teeth shows no definitive medical proof of disease). His exploitation of Tahitian women, combined with idealized paintings of their bodies, has long been seen as emblematic of colonial objectification and patriarchal dominance.

Gauguin’s mythos flourished in part due to his own writings and strategic self-promotion. His posthumously published memoir Avant et Après (Before and After) blends autobiographical anecdotes with racist and sexist assertions, attempting to recast his actions as those of a misunderstood, enlightened outsider challenging a corrupted Western civilization. Far from being a purely posthumous concern, Gauguin’s contemporaries also voiced criticism of his selfishness and peculiar sense of morality.

A New Biographical Assessment

Enter Wild Thing: A Life of Paul Gauguin (2025), the first major biographical reassessment of the artist in three decades, authored by Sue Prideaux. Rather than romanticize or outright condemn Gauguin, Prideaux urges a nuanced interpretation: “to re-examine Gauguin’s life; not to condemn, not to excuse, but simply to shed new light.”

Prideaux’s study benefits from recent scholarly breakthroughs. Notably, a 2018 analysis of dental remains from Gauguin’s grave clarified decades of speculation around his health, showing no definitive evidence of syphilis. Likewise, the 2020 resurfacing of the original Avant et Après manuscript and the 2021 release of a revised catalogue raisonné by the Wildenstein Plattner Institute have provided more precise documentation of his oeuvre and life.

In Wild Thing, Prideaux delves into Gauguin’s psychological complexity, exploring his struggles with poverty, emotional instability, and alienation. Key friendships, like his volatile alliance with Vincent van Gogh, are illuminated with greater depth. Yet Prideaux’s biography does not shy away from confronting his moral failings. While she occasionally views his misdeeds through a sympathetic lens — calling some of his memoir “silly stories,” while also noting his critiques of colonialism — the attempt is not to exonerate, but to understand the contradictions of a highly flawed man whose art has endured.

Revisiting Gauguin in the 21st Century

The reassessment of Gauguin’s legacy is part of a broader reckoning with the moral ambivalence of many historical figures once uncritically celebrated in Western culture. As museums and academia face increasing pressure to decolonize narratives, Gauguin’s place in the pantheon of modern art has become a lightning rod for debates about ethics, aesthetics, and power.

Is it possible to appreciate Gauguin’s work without endorsing the ideology it may perpetuate? Should we reevaluate or remove such art from public display? This tension between