“Exploring Marian Spore Bush’s Unique Artistic Identity”

“Who was Marian Spore Bush?” The question begins an essay by Bob Nickas, who curated the exhibition *Marian Spore Bush: Life Afterlife, Works c. 1919–1945*, currently at Karma. The artist’s first solo exhibition in almost 80 years, it feels extraordinarily modern in both style and content. Vivid, saturated watercolors of flowers and Christian allegories in the back room flirt with naïveté as much as they nod to art history. In the main space are large depictions of grim scenes (e.g., bodies immersed in water or on a raft, coupled with formidable avian creatures) that draw on the surreal and the grotesque.

So, who was Spore Bush? She was born in 1878 in Bay City, Michigan. She studied dentistry at the University of Michigan and was among the state’s first woman dentists. After her mother died in 1919, she used a Ouija board to contact her, and began receiving messages from deceased artists urging her to take up painting. The next year, she left her dentistry practice and moved to New York to dedicate herself to art and charity work; while organizing a soup kitchen, she met and eventually married millionaire Irving Bush.

It’s the kind of compelling narrative the art world — or just about any audience — devours: rags (or middle-class) to riches, spiritualism, obscurity, and rediscovery, all in one fascinating figure. Hilma af Klint’s 2018–19 Guggenheim survey resurfaced the narrative of the self-taught, visionary woman artist, often unknown to or forgotten by the art world until her posthumous or late-life “discovery,” as a popular trope. It’s easy to read Spore Bush’s story and situate her in this lineage, and the exhibition essay does so — along with af Klint, it cites Agnes Pelton, Emma Kunz, Paulina Peavy, and Gertrude Abercrombie, disparate artists whose notable commonalities are their spiritualist leanings and their gender.

There’s no doubt that Spore Bush and her work deserve recognition. But this framing, particularly when little literature on her exists, should raise some questions. Who acts as the discoverer, who tells the story, how do they tell it, and what are its ripple effects?

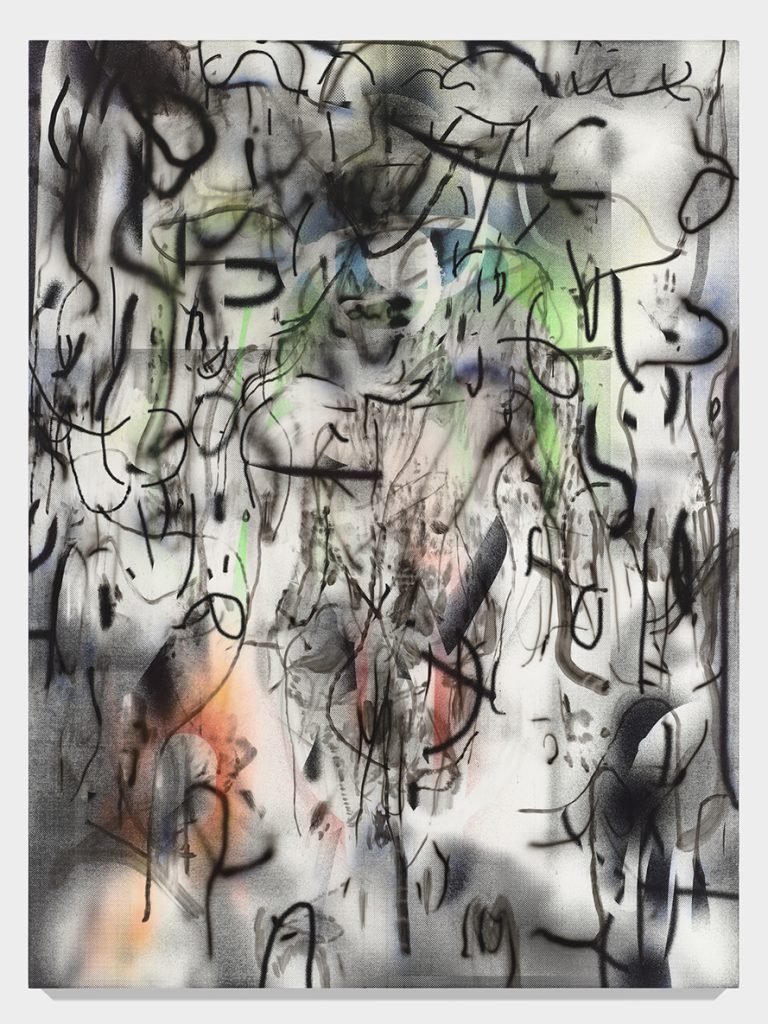

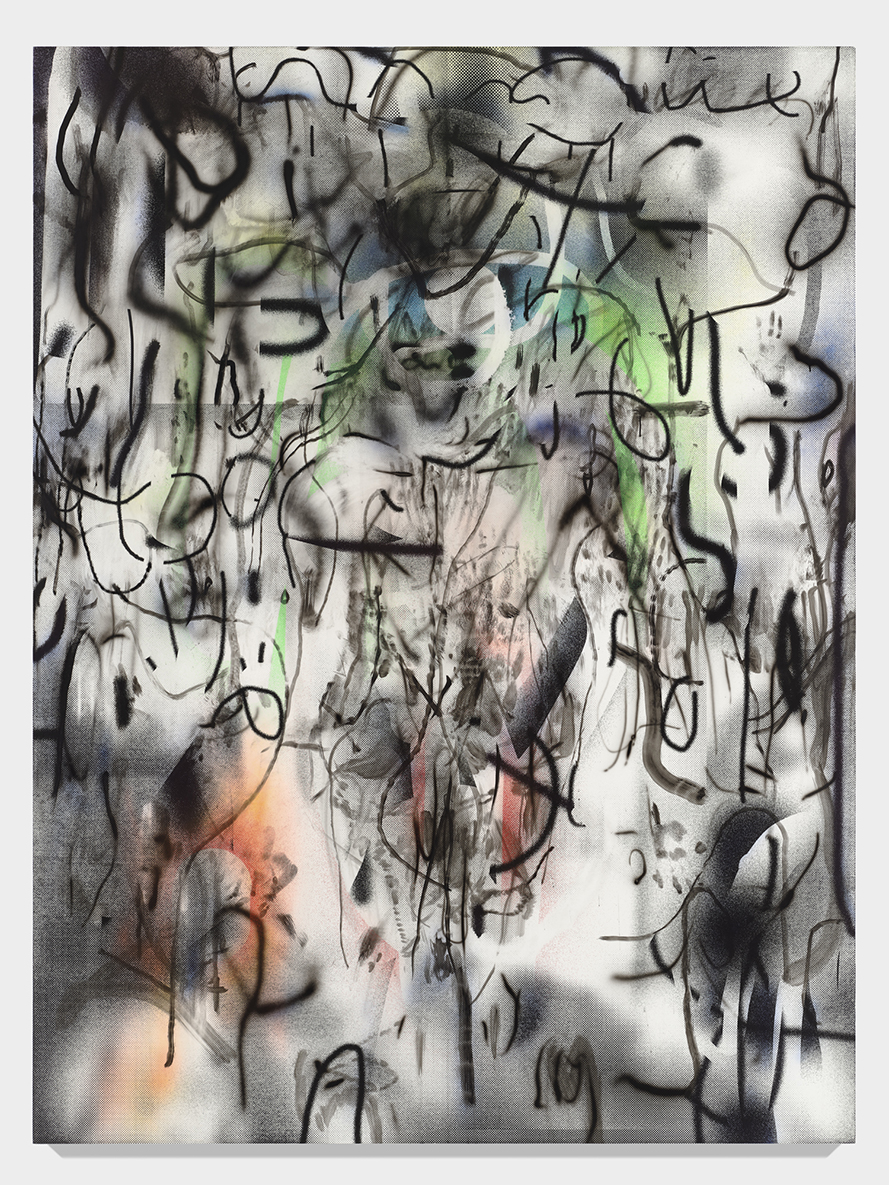

Thematically, her late mostly grisaille paintings bring to mind a different set of artists, including Goya, Otto Dix, and Käthe Kollwitz, whose art addresses violence, struggle, and salvation. Stylized birds occupy the bulk of the composition in multiple pieces from 1933 to ’43. In the United States, those dates span the Great Depression and midway through World War II, a fraught period rich with those same themes.

In “The Gaunt Bird of Famine” (1933) — a stunning painting, but not the show’s most dramatic — a giant whitish bird, rendered in thin gossamer lines that arc into graceful points, looms large against a solid black sky. Below, in the same dirty white, is what looks like a village. Spore Bush articulates it loosely and thickly, but realistically enough that it feels separate from the sky. The divide suggests a symbolic menace sweeping over the real world.

Two similarly striking birds, rendered in black against a cloudy gray sky, nearly meet at the center of “The Pawn Broker (Three Vultures),” from the following year. Below the rigid horizon line is a body of black water. A face, just above the surface, looks up at the birds, fearfully or dolefully; chains are visible around the person’s neck. The show’s standout is “The Avengers” (1943). Here, a winged figure flies close to a dead tree, from which three bodies hang. The dark, undulating ground resembles both earth and water, a stark contrast with the oceanic turquoise sky.

Spore Bush herself described her art as prophetic and guided by the spiritual forces she called “They” or “the People.” Edward Alden Jewell’s 1943 *New York Times* review, for instance, quotes her as saying: “They move my hand up and down and onward across and sideways in all directions.” Though this automatic process might echo that of af Klint, Peavy, and others, defaulting to such comparisons defangs the art and erases its cultural context. A more substantive comparison is the oversized vultures that recur in Goya’s *Disasters of War* print cycle (1810–20), in works like “The Carnivorous Vulture” and “The Consequences.” Likewise, her early allegorical painting series, in which a bearded figure in an amethyst cloak communes with animals, reminded me of art books by Oskar Kokoschka and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, in which loose, colorful