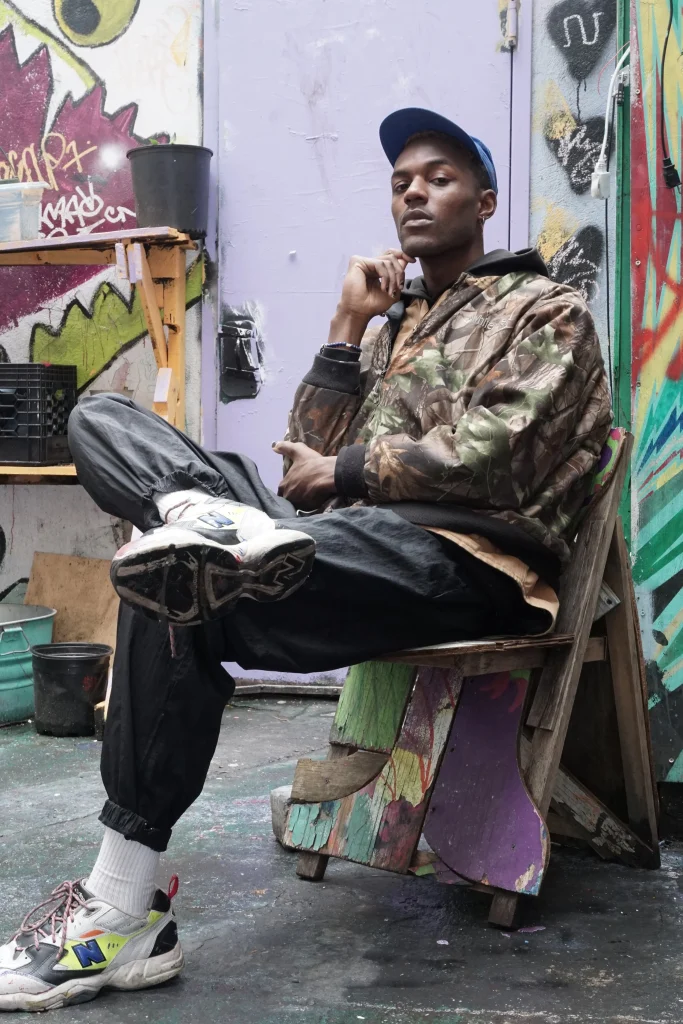

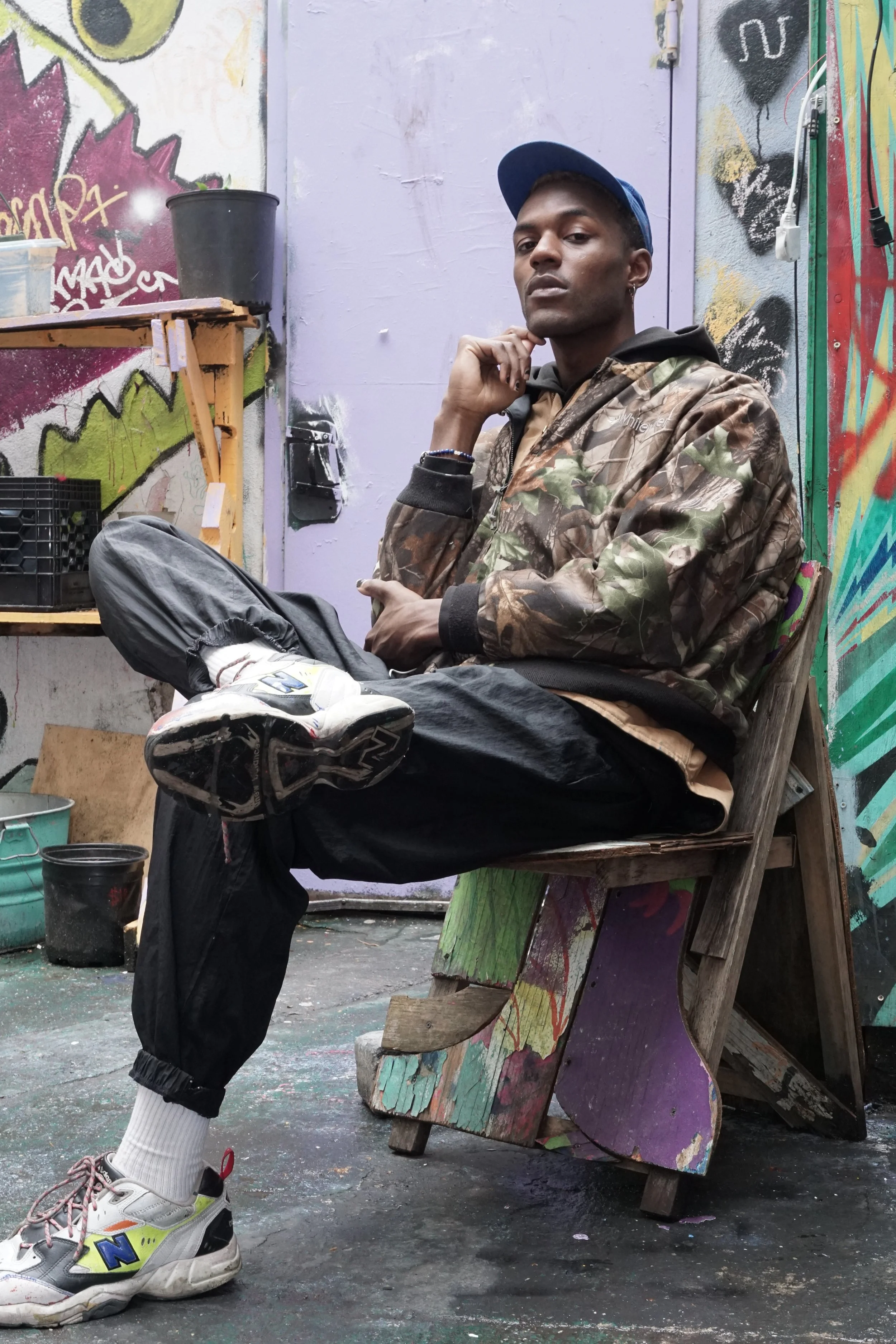

Arewà Basit Discusses Her Amy Sherald Portrait and Transforming Trans Joy

In the international queer community, Arewà Basit is known as a dancing, singing don-diva who makes music, performs in drag, and co-leads the Black queer production organization Legacy. These days, she’s also making headlines for being the subject of a “controversial” artwork by Amy Sherald. The controversy in question: a painting depicting her as the Statue of Liberty in a pink bob. In July, Sherald pulled her exhibition American Sublime from the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) in Washington, DC, over concerns that the institution would censor her painting of Arewà. Amid the nation’s descent into fascism, “Trans Forming Liberty” (2024) calls into question whether institutions represent the state or the people — and whether they’ll ever learn from their past.

The Dallas-born musician, performer, and artist is no stranger to adversity. In an interview with Hyperallergic, Arewà explained that teachers often labeled her as unruly and disruptive for her “larger-than-life personality” and “ambition to entertain and to express.”

“Being a queer kid in Texas, I was often reprimanded for just existing,” Arewà recalled. “I was disciplined for being too effeminate, for getting attention that my family or people thought was unwarranted.”

That same repressive impulse may have influenced the NPG to allegedly consider excluding Sherald’s portrait of Arewà from the show. (A representative for the Smithsonian Institution previously told Hyperallergic that it “could not come to an agreement with the artist.”) Days after Sherald withdrew her exhibition, “Trans Forming Liberty” graced the cover of the New Yorker; on August 21, the White House included the painting on a hit list targeting 26 artworks and shows depicting queer, trans, and migrant experiences as tools of so-called “divisive narratives.”

Arewà recognized that the virality of this story speaks volumes about the blatant attacks on trans people across the country and the ways they are often sensationalized in the media and that “the narrative of being visible as a Black, queer trans individual has never been more complex.”

“America likes to tell Black people what kind of a Black person they think they should be,” she said. “I think this country was gonna have an issue with a Black trans person being in the same museum as all of the presidents.”

Arewà first gained mainstream recognition in 2019 after joining the first all-queer cast of the dating show Are You the One?. Though she balked at the performative aspects of reality TV, she knew her presence would make an impact on young trans people who don’t get to see themselves on screen — particularly in a media ecosystem that chews up Black trans femmes, capitalizes on them, and spits them out. She sings about this experience on her EP Archive, which drops on November 11, drawing from a performance she gave on Fire Island, a queer getaway known for being overwhelmingly White and cis. Like many of her trans sisters, she felt loved and embraced during the day and discarded by night.

“The people who told me I was special were most often Black people,” Arewà said, reflecting on the role models who shaped her upbringing. “And so I learned from an early age that the only thing that was gonna protect what makes me special is to embrace it.”

Arewà drew a comparison between the scrutiny of her portrait and historical reactions to other muses and models, namely the socialite Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau in John Singer Sargent’s infamous “Madame X” (1884), which scandalized the public and art critics upon its debut at the Paris Salon.

The painting, Arewà explained, was the original reference for “Trans Forming Liberty,” which she was chosen to model for after Sherald put out a casting call for a Black drag artist. “What she found was a video of me performing ‘I Can’t Stand the Rain’ by Ann Peebles,” Arewà commented.

In the artist’s New Jersey studio, Sherald and Arewà tried a shoulder-length hairstyle they both agreed was too “Michelle.” They landed on the bright pink wig as a symbol of Arewà’s identity. At first, Arewà said she placed her hand on a table as in “Madame X,” but once she struck a pose and lifted her hand like Lady Liberty, the direction became clear.

But what does it mean when the subject becomes a spectacle because of her identity? In Sherald’s body of work, “Trans Forming Liberty” is a standout, in part because of the divine feminine form and adornment of the sitter in comparison with her other grisaille paintings. Still, Arewà insists on the subjectivity of portraiture, explaining that “the painting is not a reflection of me, it’s a representation of me.”

Queer and