The Largest Animal Sanctuary in the Nation Functions with a Motto to ‘Rescue Them All.’ How Can That Be Seen as Controversial?

Best Friends Animal Society features an extensive campus nestled in Utah’s canyons, yet its impact has expanded to influence nearly every shelter across the nation

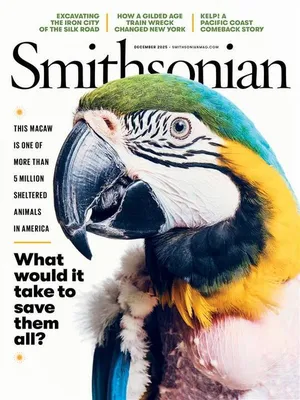

Chubby the macaw came with self-plucking injuries, often due to stress, lack of stimulation, anxiety, or life transitions. At 22 years old during the 2025 photo, Chubby has since been adopted.

Shayan Asgharnia

In 1982, a balding, bearded man named Francis Battista drove through a canyon near Kanab, Utah, in a worn blue hatchback. He looked up at the impressive red cliffs rising above the fields of junipers and pines. “It’s magical!” he mused. When he looked down, he spotted a locked gate bearing a sign: $3 for a tour map. He handed the nearby woman the cash.

The gate led to a ranch, and spontaneously, Battista inquired if the land was for sale. “Could be,” she answered. The site had once attracted many filmmakers for westerns. Nearby, episodes of the TV series “Gunsmoke” were filmed, along with various movies, and the property’s owners, a cohort of businessmen from Kanab, were attempting to manage a tour venture. However, it was failing, and several investors were eager to sell off the estate. Thrilled, Battista returned to a shared homestead in Arizona with 26 friends and a multitude of 200 animals including dogs, cats, bunnies, burros, and birds.

Battista and his companions followed a new spiritual path named the Foundation Faith of God. The faith’s founder was a former Scientologist who separated from the church and merged Christian millennialism with elements of psychotherapy. Their group provided support in children’s hospitals, prisons, impoverished communities, and other areas where they felt their assistance could be beneficial. “It was all about connecting with the angels in our lives,” Battista recounted to me.

Battista and his team operated an animal rescue ministry. They were an eclectic mix—architects, graduates from Oxford and Cambridge, creatives, writers, college dropouts, an engineer, a CPA, a real estate professional, a wealthy heiress, a British actress, and an Afro-Cuban musician—who collaborated to purchase the small ranch in Arizona for the Foundation Faith. After rescuing a few hundred animals, they swiftly filled their space to capacity, prompting Battista to search for additional land.

Francis Battista—with his dog Billy—first discovered the land for the sanctuary in 1982. “It had this sense of openness and air and space,” he recollects. “I truly felt transported there.” Shayan Asgharnia

By 1984, the collective had accumulated enough funds for a down payment on the Utah ranch, moving in with their 200 adopted pets. Over the decade, as they concentrated on creating what would evolve into the Best Friends Animal Society, the religious organization began to fracture. “The Foundation Faith ran its course,” Battista remarked recently. “Everything started to revolve around the animals.”

Presently, Best Friends operates as a secular entity, managing the nation’s largest sanctuary for abandoned and abused pets, complemented by a national network of aligned shelters. The Utah site spans almost 6,000 acres and provides refuge to about 1,600 animals, including dogs, cats, horses, pigs, bunnies, and birds. Its size creates distinct neighborhoods: Dogtown, Cat World, Horse Haven, and others. Each creature receives dedicated medical and emotional attention, ideally reaching a condition suitable for placement in a permanent home. Each year, over 300 staff members are joined by 6,000 volunteers and 40,000 visitors, many staying for extended periods to engage with and care for the animals. So popular is the site that the management acquired and renovated an abandoned hotel nearby and maintains a fleet of vans for transporting animals and visitors.

Did You Know? What is the oldest animal shelter in the United States?

- Animal pounds in the U.S. can be traced back to the Massachusetts settlements of the 1600s.

- The oldest true animal shelter in the country, the Women’s Animal Center in Philadelphia, was founded in 1869.

Best Friends CEO Julie Castle with Yule, a young mixed-breed dog. Yule was moved to the Best Friends Lifesaving Center in Salt Lake City, where he was adopted. Shayan Asgharnia

Scott and Marnie, two mixed-breed dogs around a year old, frolic in the sanctuary’s Dogtown, home to about 400 dogs and puppies regularly. Shayan Asgharnia

However, Best Friends has also stirred controversy. It was one of the first animal welfare organizations to publicly oppose the common shelter practice of euthanizing animals to alleviate chronic overcrowding. Their rallying cry is clear: “Together, We Can Save Them All.” Increasingly, Best Friends has pursued this vision on a national scale—financing training initiatives, integrating its staff within struggling shelters, and providing grants to those sharing its mission. Through this journey, Best Friends has emerged as a significant voice in the national dialogue concerning animal welfare, standing alongside groups like the Humane Society and the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Yet critics assert that its methods can be too rigid and at times counterproductive. “I commend them for challenging the industry to step outside its comfort zone,” Julie Levy, a shelter medicine expert at the University of Florida, remarked to me. “But occasionally, those strategies can backfire, necessitating a reconsideration of approach.”

In response to these critiques, Julie Castle, the society’s CEO, reaffirmed the group’s central belief: Our pets are our best friends. Why should we condone ending their lives?

The vibrant red rock region of southern Utah has seen its fair share of inhabitants through the ages. The land was once home to the Ancestral Puebloans, who lived there millennia ago, etching enigmatic petroglyphs onto the rock faces. A Spanish expedition traversed the area in 1776, in search of a trade route connecting Santa Fe and Monterey. A century later, ten Mormon families settled, founding the contemporary town of Kanab. The early 20th century witnessed a golden age of filmmaking. By the time the sanctuary arrived, that era had largely faded, leaving the canyon tranquil.

Cyrus Mejia, a co-founder and board member of Best Friends, recounted his initial impressions of the ranch. “There was nothing,” he stated. “No infrastructure, no roads, no electricity, no telephone.” The group combined their resources, obtained a few donated trailers, and began constructing a bunkhouse. They relied on DIY manuals to educate themselves on building techniques. (A friendly debate among the founders continues over whether they used Reader’s Digest or a Time/Life manual.) They engaged a local individual to assist them in digging wells.

Their plan was to accept animals that had exhausted their possibilities and faced extermination. “We aimed to provide them with room and time to recuperate,” Mejia shared. Soon after, animals began to arrive. People would bring unwanted pets; local law enforcement would deliver strays.

The landscape surrounding Best Friends Animal Sanctuary. The area was once a prominent filming location for Hollywood westerns. Nowadays, the sanctuary stands as a significant tourist destination. Shayan Asgharnia

Bobbie, a 10-year-old lionhead rabbit, is approaching the end of his anticipated life span. He receives electroacupuncture from veterinarian Christina Shepherd and caregiver Stephanie Vosburgh here. Shayan Asgharnia

The situation shifted dramatically after one dog escaped from the sanctuary and appeared at the local pound. The sanctuary team discovered the pound was a grim, tin-roofed prison, stifling in the summer and frigid in the winter. A veterinarian would visit weekly and euthanize any animals not adopted. This instance was a microcosm of a larger issue confronting them! Battista spoke with the mayor of Kanab, detailing that he and his friends were freshly arrived in the area, with an abundance of land, willing to take over animal control. “Sure,” the mayor agreed.

“It’s just a small town,” Battista and his associates thought. “How bad could it get?”

They would soon learn otherwise. The animal control district extended beyond Kanab’s boundaries; it included surrounding towns and counties, covering thousands of square miles. When word spread that a group of hippies was adopting animals, the influx began: strays, escapees, hoarding victims, and pets their owners could no longer care for. “Once, someone contacted us regarding some cats under their trailer,” Battista recalled. “By the time we left that location, we had picked up 65 cats.”

From the outset, Battista and his friends were dedicated to doing things differently than conventional pounds, rooted in 19th-century practices established for public health protection. Pounds initially functioned as facilities for rounding up stray dogs suspected of carrying rabies, destined for execution. Although this was brutal, it represented an edge over allowing individuals to shoot or bludgeon dogs on the streets. By the 1930s and 1940s, rabies vaccinations for dogs became widely accessible, diminishing risk. The population crisis began to ease in the 1970s due to affordable spaying and neutering. Shifting societal viewpoints, favoring pets as family members, also played a role, reducing abandonment rates. Nevertheless, America’s shelters were inundated, resulting in at least 13.5 million cats and dogs being euthanized annually, as per the Humane Society.

Best Friends firmly opposed this practice. Their mission is to rehabilitate every feasible animal, resorting to euthanasia only when a veterinarian deems an animal irreparable. For those animals merely occupying space or requiring additional recovery time, Best Friends asserts that “euthanasia” is a euphemistic term. They prefer the blunt and straightforward term “kill.”

Due to this philosophy, it did not take long for Best Friends to accumulate 2,000 animals—far exceeding the number of people ready to adopt them. Funds dwindled. Faced with the risk of their animals not receiving food (not to mention their own hunger), the founders resorted to begging—or “tabling,” as they termed it. They traveled hundreds of miles to cities like Salt Lake City, Denver, Las Vegas, and others, setting up tables outside grocery stores and shopping centers, showcasing images of joyful animals, sharing their narrative, offering animal care advice, and placing a coffee can for donations. It became a daily struggle for pennies.

Fortune turned on a day in Los Angeles when Maria Borgel-Petersen, the spouse of director Wolfgang Petersen, stopped at their table. Touched by Best Friends’ mission, she enlisted her celebrity associates to promote the cause and aid in fundraising. In 1992, a co-founder with publishing expertise launched a magazine featuring a subscription list and membership fees. Thousands signed up.

Vincent, a 2-year-old Vietnamese potbellied pig, was transferred to the sanctuary from New Mexico in late 2024. Many animals at Best Friends experience ailments—in his case, missing ears. Shayan Asgharnia

Caregiver Rosalie Wind interacts with Vincent the Vietnamese potbellied pig, who is deaf. Shayan Agharnia

Then, during the summer of 1993, Caroline Marcus, a prominent dog walker for celebrities, stopped at a table hosted by Battista and his future spouse, Silva. She collaborated with them to arrange a fundraising event and invited a plethora of A-list stars.

That fall, Marcus and Best Friends organized a benefit at Chateau Marmont, one of the most luxurious hotels in the area. Battista and his team were so financially strained that they borrowed formal attire from their Hollywood acquaintances. “We felt like ‘The Muppets Take L.A.,’” he recalled. More events unfolded—year after year.

“They attended all the finest venues,” noted Silva Battista. “The Hollywood Roosevelt, the Hollywood Palladium.”

“One time we hosted Charlize Theron, Laura Dern, Hilary Swank, and Debra Messing all at the same gala,” her husband added, still a touch starstruck.

By 1995, Best Friends initiated local “Strut Your Mutt” adoption events across various cities. In 1999, they launched an annual mega-adoption event in L.A. (The latest occurred at the Rose Bowl.)

With donations and grants flowing in, the organizers could sustain the animals and continue construction. Each zone—Dogtown, Cat World, Horse Haven, Marshall’s Piggy Paradise, Bunny House, and Parrot Garden—was outfitted with numerous buildings and ample outdoor area, fostering stimulation and comfort for the animals. They developed a wildlife section, a veterinary clinic, and a welcome center, along with acquiring a fleet of vans. They also increased their staffing, and in 2001, began hosting conferences to disseminate their message and engage with fellow shelter leaders on achieving their mission.

Caregiver Landon Schobert with a young dog named Carolina Reaper. The dog has since been relocated to RezDawg Rescue, an organization working with Indigenous and rural communities. Shayan Asgharnia

Caregiver Kaila Dondlinger attends to Pepper, a 26-year-old scarlet macaw. Many birds in Best Friends’ Parrot Garden have had several owners and even outlived some of them. Shayan Asgharnia

Then tragedy struck, catapulting Best Friends into the spotlight. In 2007, law enforcement in Virginia raided Bad Newz Kennels, a dogfighting operation co-owned by NFL quarterback Michael Vick. The animals suffered severe abuse—forced to run until exhaustion, whipped with chains, deprived of food, electrocuted, pitted against one another, and killed if found inadequate in aggression. While the public held vague notions of dogfighting, this extreme case involving a sports celebrity brought the matter into sharp focus.

Most assumed that dogs trained for fighting were too dangerous to allow to live. The Humane Society, among others, recommended euthanasia. Best Friends, however, had different plans and took in 22 of the most traumatized animals. (Another advocacy group from the Bay Area rescued ten others.) The caregivers argued that these dogs were more frightened than ferocious. Under the guidance of animal behavior expert Frank McMillan, Best Friends assessed each dog and devised individual rehabilitation strategies. “Within weeks, some of them were coming out of their shells, having fun with toys and interacting with people,” Michelle Weaver, who oversaw the initiative, shared. Ultimately, 13 of the dogs were rehabilitated successfully for adoption, while nine lived out their days at the sanctuary. None of the Bad Newz rescues that arrived at the sanctuary had to be euthanized.

National Geographic celebrated the program in “DogTown,” a television series about Best Friends. As the Washington Post noted, “The dogs became ambassadors, wagging their tails as proof of what can be achieved through rescue and rehabilitation.”

Visiting the sanctuary resembles an excursion in a national park, with its breathtaking landscapes and rustic-style buildings. The welcome center features exhibits, trail maps, a registration desk for tours, and a gift shop. A dirt road meanders through the canyon, with pull-offs for the distinct areas and an award-winning plant-based café. Along the path, you might spot volunteers walking dogs or pushing carts with cats. Some visitors arrive for adoptions, gaining time to interact and bond with prospective pets.

Every animal arriving at the sanctuary undergoes an intake procedure encompassing a medical assessment, vaccinations, and any needed treatments, including surgeries. They are also spayed or neutered and quarantined to ensure they are disease-free. Following this, a behavioral assessment is conducted: Is the animal aggressive? Timid? Does it interact well with other animals and humans?

The animal then receives treatment through behavioral protocols—essentially therapy for them. Weeks, months, or even years can pass before an animal is ready for adoption; if that’s not feasible, it can enjoy its life in a serene, stress-free environment.

During my short stay at the sanctuary, I met Melissa McCormic, a senior manager at Dogtown, holding a degree in biopsychology. She led an onsite team of about 30 caring for over 420 dogs, focusing on social acclimatization. “We strive to integrate them into a play group,” she explained. Each new dog is placed in a small solo enclosure adjacent to the larger group area, while its body language is observed. If it appears comfortable, it’s introduced to a small pack with a “greeter dog”—a sociable, low-energy dog skilled at helping other dogs feel at ease. A team member is always present in the yard.

Kit, a Siberian husky mix with a neurological condition, was found abandoned alongside her brother, Caboodle, on the roadside in Missouri when they were eight weeks old. Due to mobility difficulties, Best Friends caregivers wheel them around the sanctuary. Shayan Asgharnia

Caboodle, a Siberian husky mix who arrived at the sanctuary with his sister, Kit, came with balance issues and received specialized physical therapy at Dogtown. Shayan Asgharnia

McCormic and her team embrace an approach among dog trainers known as LIMA: Least Intrusive, Minimally Aversive. This model aims to alleviate fear in animals already stressed from confinement or maltreatment. They employ a training clicker along with treats to recognize and reward positive behavior, such as responding to calls or to distract dogs exhibiting negative behavior, such as overly aggressive resource guarding. The lack of a reward might suffice to deter unwanted behavior, or they may utilize a squirt of water to interrupt it. Team members log daily notes about each animal. The process is gradual, the pace depended on the dog. Sometimes trainers leash a dog near the front door and reward it simply for remaining calm. Days later, they may walk a few feet from the building, enabling the dog to slowly gain faith that they will return, and eventually venture further away. When a dog is truly at ease, the staff encourages volunteers to take it on walks or car rides.

Gilmore, a plump tan dog, had been attacked by other dogs in a shelter in New Mexico and still struggled to adapt in a playgroup. He remained in his own private kennel and outdoor run. He was timid around humans but not terrified. “You can briefly pet him, but he’s not too keen on it,” McCormic remarked. She and her team worked to bolster his confidence through “nose work,” among other techniques: hiding his food while allowing him to use his nose to find it. As they gradually exposed him to people and other dogs, he showed progress. McCormic noted he was adoptable but would need a special owner, “someone who appreciates a very shy dog.”

Upon visiting Cat World, around 550 cats were residing in its 11 buildings and outdoor spaces. Each cat needing rehabilitation was assigned a “pathway to progress”—a series of goals set for 30, 60, and 90 days, with daily progress registered in a logbook.

Pipkin, for instance, was an amiable tabby with an aversion to human hands. “She’d approach and rub against you, but if you reached out to touch her, she’d react aggressively,” explained Amy Kohlbecker, who was the director of Cat World. Pipkin’s initial goal for 30 days was simply allowing a human to come close. In 60 days, she aimed to permit a trainer to reach her with a plastic hand on a stick. Kohlbecker noted they opted for a fake hand to avoid bites and scratches. Eventually, Pipkin achieved her 90-day target: accepting petting from someone without aggressive reactions. The ultimate goal: “To get her adopted into a calm, understanding home.” (Pipkin was adopted shortly after my visit.)

Percy, a cat suffering from feline immunodeficiency virus and feline leukemia virus, enjoys a treat. Shayan Asgharnia

Best Friends strives to keep even the sick animals comfortable and provide them with a dignified death. Claudius, shown at one year old in this image, later succumbed to large cell lymphoma. Shayan Asgharnia

Evelyn arrived at Best Friends’ Cat World as a kitten. She suffers from Manx syndrome, a congenital disorder that causes her to be incontinent for her entire life. Shayan Asgharnia

Another cat named Charlee had been part of a therapy initiative in a women’s prison until one day an inmate began to kick her before a guard intervened. This incident occurred over a year before my visit, yet Charlee continued to display trauma. She manifested this by biting her own side until it bled. Charlee wore a plastic recovery cone akin to those used for dogs post-surgery. She adored being petted, behaving like a well-adjusted cat. However, once caregivers removed the cone, Kohlbecker explained that Charlee resumed biting herself. “We’ve conducted every conceivable test to determine if there are physical issues,” Kohlbecker stated. “It is more psychologically affected now.”

Despite such challenges, Cat World exuded a lively vibe. Different houses and outdoor spaces catered to every need: incontinent cats, those with neurological issues, saved ferals, cats with feline leukemia virus, and healthy cats. The majority of animals were available for adoption.

Kohlbecker was speaking with me while surrounded by healthy adolescent cats when a tour group entered. The visitors were enchanted by the sight of kitties navigating obstacles, racing through tunnels, swatting at toys, and tumbling over one another—pure feline charm. It wasn’t long before guests found cats nestled in their laps.

“Oh, just look at these little ones!”

“Mom, look over here! They’re adorable, so precious!”

“I’m drawn to that black cat!”

“If you fall in love with one of these sweethearts, our adoption specialists will ensure you’re adequately informed before making a decision,” came the assurance from the tour guide.

Exotic birds are potentially the least adoptable in the sanctuary, particularly larger parrot species. They enjoy long lifespans (some exceed 50 years), which often means they may outlive their owners. Additionally, many exhibit challenging behaviors. Cockatoos are known for their vocalizations that can reach over 130 decibels, enough to impair hearing. Certain parrot species possess bites capable of exerting over 300 pounds of pressure per square inch, which can severely injure fingers.

Three lilac-crowned Amazons, named after characters from the show “Buffy the Vampire Slayer”: Spike, 6; Giles, 29; and Cordelia, 39. All three have since been adopted. Shayan Asgharnia

The sanctuary’s Parrot Garden harbors exotic birds of all shades and sizes. Beepo, a 36-year-old blue-and-gold macaw, was adopted shortly after this photograph was captured. Shayan Asgharnia

Matthew, a 27-year-old hybrid macaw with avian bornavirus, is recognized at the sanctuary for swaying and “singing” along to melodies ranging from Celine Dion to Gregorian chants. Shayan Asgharnia

These birds are never entirely domesticated, according to Elle Greer, who supervises the Parrot Garden. While dogs and cats have coexisted with humans for millennia, some exotic birds may be only a generation or two apart from their wild counterparts. “You’re dealing with a wild animal that’s exceptionally intelligent and has some of the most sophisticated social structures we’ve studied,” Greer noted.

Placing these birds in isolation within a cage drives them to madness; estimates suggest that at least 10 to 15 percent of captive parrots exhibit self-destructive behaviors. This may manifest as compulsive grooming, termed “barbering,” or pulling out feathers, or self-mutilation leading to bleeding. Numerous caged birds suffer from physical ailments, such as heart disease and osteoporosis, resulting from poor nutrition, lack of sunlight, and insufficient exercise.

In Parrot Garden, around 140 birds reside in interconnected indoor and outdoor aviaries. Their calls are so loud that earplug dispensers are mounted along the walls. As with the other trainers, Greer and her team set progress plans for the birds, using positive reinforcements and engaging activities to prompt them away from harmful conduct.

Matthew, a hybrid macaw, was surrendered by an elderly woman unable to care for him. He was a riot of colors—blue, yellow, red, and green—with a white face and black-patterned markings around his eyes. He arrived with varied symptoms, including seizures that made him fall off his perch and lay motionless on the cage bottom. His bites were sudden and powerful enough to slice through tin. “If he were a dog, a muzzle would be necessary,” Greer asserted. He also engaged in feather picking, which his trainers sought to mitigate by providing distractions. They increased stimulation by requiring him to forage for meals, covering his food dish with shredded newspaper—a novel experience for a bird that may never have encountered shredded paper previously.

Matthew was endearing in his own manner. He had a taste in music and particularly enjoyed popular tracks from the 1990s, especially Whitney Houston’s ballads. “He sways to the music and sings, ‘La-la-la-la-la,’” Greer said. “It’s incredibly charming.” However, Matthew’s seizures and unpredictable biting behavior made him a challenging candidate for adoption.

Rusty, a 6-year-old male Oberhasli goat, is seeking a home. According to the sanctuary, “He serves as a strong leader for his herd and is known to even resolve conflicts among them.” Shayan Asgharnia

Angels Rest, a memorial site within Best Friends Animal Sanctuary, hosts monthly blessing ceremonies where the public can honor their pets’ lives. The sanctuary’s webpage provides memorial wind chimes, bricks, and markers for sale. Shayan Asgharnia

Jen Reid, senior manager overseeing horses at the sanctuary, with Emma Dean, a mare saved from the shores of Lake Powell. Her foal, also rescued, has found a new home. Shayan Asgharnia

At Horse Haven, I encountered Emma Dean, a reddish-brown mare who had survived a harrowing experience. She and her foal had been grazing on the shores of Lake Powell when swiftly rising waters from an unusually heavy spring runoff trapped them for weeks—water in front of them, cliffs in the rear. Horses, being prey animals, are naturally nervous, and Emma Dean’s ordeal heightened her anxiety. The foal thrived and was adopted. However, Jen Reid, the senior horse manager, recognized Emma Dean’s nerves were tightly wound. For weeks, Reid refrained from entering the pen; she would merely drop hay for the horse to nibble on without making direct eye contact. Over months, she gradually drew closer to Emma Dean, attuning to subtle signs of unease. “If she twitched an ear towards me, that was my signal to halt,” Reid recalled. Eventually, she touched Emma Dean with an eight-foot lunge stick while maintaining her distance; weeks later, she stroked her side; months after that, she fitted her with a halter; later, she began taking her for walks. Gradually, Emma Dean learned to release her fears.

When I encountered Emma Dean, she had resided at the sanctuary for a year and eight months. She displayed calm body language as we approached: gentle eyes, relaxed ears, and an un-tense mouth. She stood peacefully as Reid caressed her face, slipped a rope halter over her head, and walked her about. “Sorting this out is reminiscent of mathematics,” Reid expressed. “You begin with one plus one, then one plus two, gradually incorporating complexities until you’re tackling algebra and trigonometry.”

Best Friends’ size is notable, not just in terms of land area. Recently, the organization’s annual revenue has surpassed $173 million. The society has evolved into a marketing powerhouse, boasting a robust online presence and over 900 employees spread nationwide. In 2007, Best Friends initiated the formation of a national network of similar shelters, wherein staff members support one another. They alleviate overcrowding by relocating animals to shelters with more space and providing equipment and technical support. Throughout the 2010s and 2020s, they established a network of centers and programs in cities like Atlanta; Bentonville, Arkansas; Houston; Los Angeles; Salt Lake City; and New York City. They hired numerous new staff members to facilitate regional support centers, supplying veterinary care and management expertise.

“In 2016, we made a definitive statement: ‘We are committed to achieving a no-kill status for this country by 2025,’” Castle shared with me. “We were keen on testing the boundaries of what could be considered saveable.” Best Friends’ stance was that no more than 10 percent of the animals at any given shelter should be deemed beyond rescue. Their interpretation of “no-kill” signified ensuring at least 90 percent of animals survived, a mission pursued with fervent dedication. Castle assembled a tech team to collect data about the country’s public and private animal shelters (they estimate nearly 4,000). They developed a digital dashboard that reveals monthly performance metrics on state, county, and individual shelter levels. (The map is accessible online and also displayed in the welcome center.) In 2024, the organization devised an algorithm utilizing artificial intelligence to anticipate rising euthanasia rates before they become a concern, analyzing demographic, economic, and social data for a region. This effort identifies shelters that fall below expectations to connect them with successful shelters or deploy a Best Friends team to assist them.

Ivy, a 9-year-old Vietnamese potbellied pig, arrived at the Best Friends Animal Sanctuary after living as a stray in northern Utah. Shayan Asgharnia

3-year-old Aberdeen was successfully adopted through the Best Friends network. Shayan Asgharnia

In 2018, for instance, Best Friends dispatched a team to manage a shelter in southern Texas. The Palm Valley Animal Society took in nearly 40,000 animals annually, yet only about 25 percent managed to survive. Best Friends assumed control of the shelter’s operations, enhancing adoptions through improved marketing and unique programs, returning lost pets to their rightful owners, and enacting measures to lessen the euthanasia rate. “After 18 months, we transitioned from euthanizing over 100 animals daily to saving over 90 percent,” stated Luis Quintanilla, who worked at Palm Valley during that period. He was so inspired that he relocated to Utah and became the senior director of sanctuary animal care at Best Friends. Quintanilla’s coworkers pointed out several additional shelters achieving similar positive outcomes.

However, not every interaction proceeded smoothly. To qualify for Best Friends’ no-kill status, a shelter is required to maintain a 90 percent “save rate,” and if a shelter falls short, it can unfortunately be labeled “pro-kill.” This stigma can deter donors, create pressures on staff, and lead to harassment of managers. “Competent leaders, veterinarians, and staff have exited the field of animal welfare entirely because of conflicts surrounding the rigid 90 percent standard,” Levy, a shelter medicine specialist at the University of Florida, pointed out.

When Paulette Dean, executive director of an animal shelter in Danville, Virginia, rejected Best Friends’ offer to intervene, the organization orchestrated a local pressure campaign featuring TV ads, a dedicated Facebook page, door-to-door canvassing, and testimonies at city council gatherings. As Best Friends criticized her shelter’s efficacy, Dean found herself “immersed in a social media nightmare” filled with harassment and threats. Katie Fine, a Best Friends representative, asserted that the organization did not intend for any such abuse to occur. Eventually, this activism did spur the city to provide the shelter with support for necessary improvements; however, Ken Larking, the city manager, described the process as fraught with needless conflict and strain. Other communities have reported analogous experiences.

Critics argue that this dogmatic approach can be detrimental to animal welfare. Shelter managers fearing the “pro-kill” label often house far more animals than their facilities can accommodate—leading to severe overcrowding that results in stressed, unhappy animals less likely to be adopted. At times, shelters wishing to avoid scrutiny may refuse intake of animals they would have otherwise accepted, leaving those animals to be abandoned, neglected, or otherwise mistreated. Daphna Nachminovitch, senior vice president for cruelty investigations at PETA, is a known critic of Best Friends. “While they may reduce euthanasia rates, they fail to diminish suffering,” she remarked.

Few would dispute that the no-kill advocacy played a critical role decades ago when euthanizing animals was commonplace. The movement encouraged innovative approaches in altering the pet sterilization culture, supporting pet owners, and enhancing adoption rates.

However, now that national survival rates hover around 89 percent, many perceive the no-kill label as overly simplistic and divisive. It does not account for the conditions differentiating private shelters which can manage their intake from public shelters that frequently cannot; or the disparities between affluent and impoverished areas, or urban versus rural conditions; for shelters facing staffing shortages versus those without.

Cache, a 24-year-old Moluccan cockatoo. The team at Parrot Garden interact with the intelligent, vocal birds by playing music, dancing with them, or reading them stories. Shayan Asgharnia

Climate factors can also influence the situation since warm weather enables strays to survive and proliferate. For instance, a shelter in Houston, grappling with about one million stray dogs and cats on city streets, receives around 20,000 animals each year. “What options do they have with all these animals?” pondered Mike Keiley, vice president of the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals-Angell Animal Medical Center. Regrettably, he added, euthanasia sometimes becomes necessary.

Keiley’s own shelters boast a commendable 94 percent placement rate. Nonetheless, he is reluctant to adopt the no-kill designation, as he believes it generates more discord than solutions. He frequently debates with Best Friends’ leaders over their philosophies. But he actively participates in their shelter collaborative program, accepting grants to partner with under-resourced shelters in South Carolina. “We share a mutual goal,” he clarified.

Best Friends seems to align with many critics on another front: the desire to transform shelters into community resource centers. Increasingly, some shelter managers are engaging pet owners in dialogue about their reasons for surrendering their pets and offering assistance to help them retain their animals.

Many shelters are now providing grants for pet owners to cover routine procedures such as spaying, neutering, and vaccinations, or even offering these services at no cost. If the issue lies with a pet’s behavior, some shelters connect individuals with training services. When landlords disallow pets, shelter or animal welfare organizations may mediate negotiations to attain a compromise. Furthermore, the majority of shelters now offer foster programs where people can temporarily house an animal to alleviate overcrowding, similar to how foster parents might take in a child.

Castle, who joined Best Friends 27 years ago in a low-paid, multifaceted role, expresses optimism about the strides made across the country. Although the organization did not achieve its goal of getting every U.S. shelter to meet its no-kill standards by 2025, they estimated that about two-thirds have met the criteria, with hundreds more approaching that threshold. Castle is confident they will reach that target, regardless of whether their methods appear heavy-handed.

“Shelters have historically been viewed negatively,” Castle stated. “We’re dedicated to reshaping them as life-saving centers with positive outcomes. They will become places that evoke smiles upon entry.”