Interview: Investigating Postcolonial Identity via Hybrid Artworks by an Artist

Throughout his three years at art school, Sid Pattni did not acquire the skill to paint his own skin tone. Portraying white skin felt more intuitive to him than brown skin, and it was after completing his program that he began to question this phenomenon. At this juncture, the Australian artist established the groundwork for his creative endeavor, steering toward post-colonial frameworks that could more aptly address his concerns regarding diaspora and displacement.

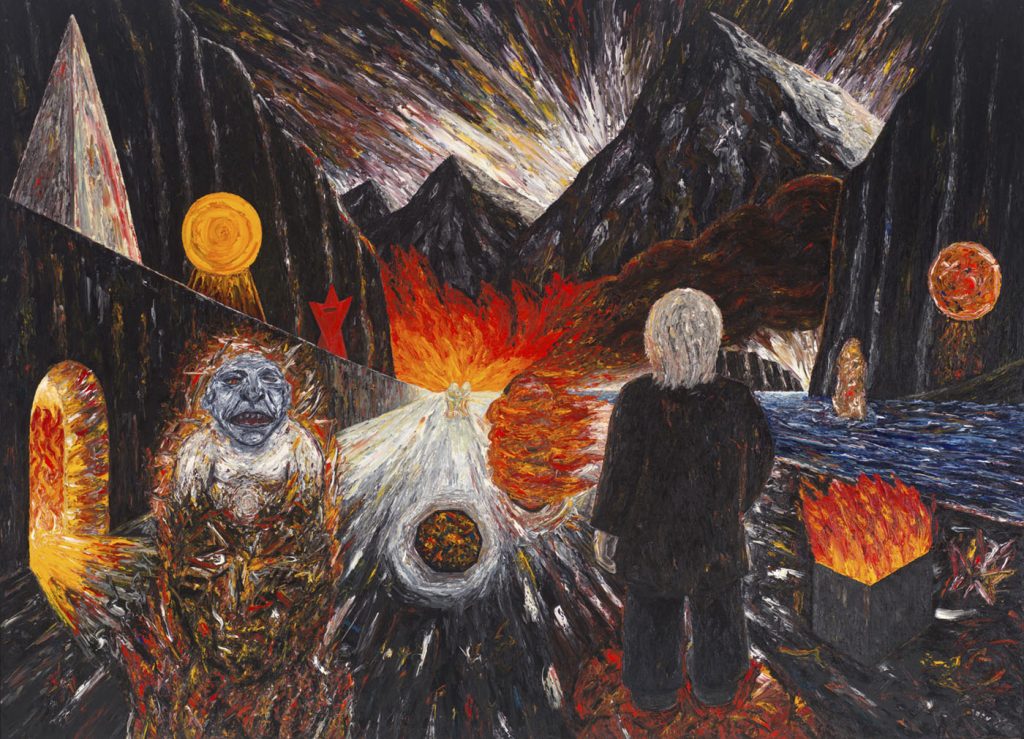

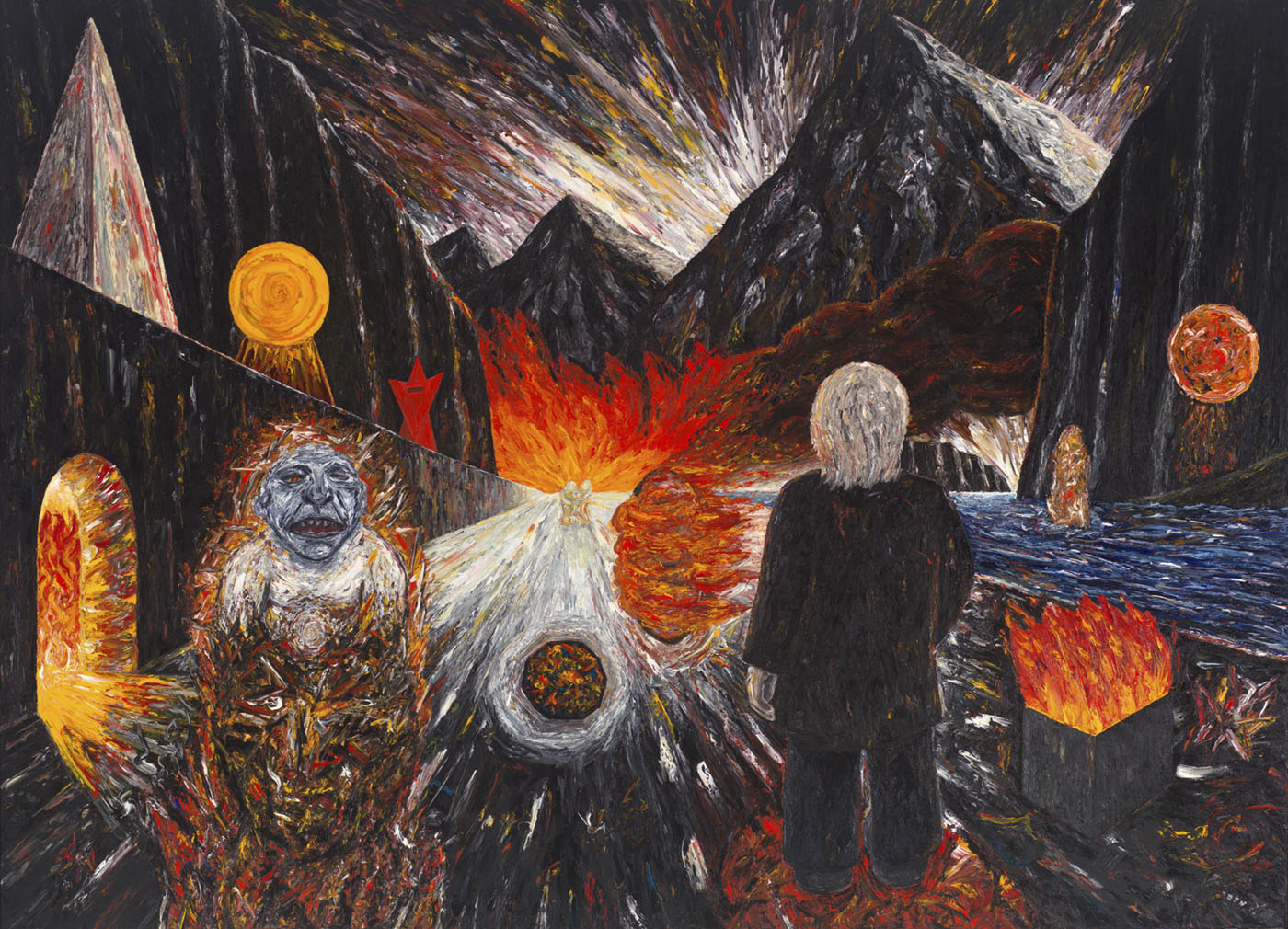

Currently, Pattni is recognized for his paintings that resurrect imagery of empire, while simultaneously “dismantling and reconfiguring” the aesthetic languages that support them. More often than not, this “dismantling” manifests through Mughal miniatures, an artistic tradition originating from South Asia characterized by flat colors, figures, floral borders, and grand themes. Although Pattni’s miniatures may center around these stylistic traits, they also include colonial figures that lack faces rather than being endowed with identities. The contrast is striking: vibrant, elaborately patterned frames enclose black voids at the heart of Pattni’s canvases. In these spaces, we find no remnants of empire, save for small eyes observing from the shadows.

“By confronting the visual legacies of empire, my work aims to reveal the common strategies of control, categorization, and representation underlying colonial systems worldwide,” Pattni shares with My Modern Met. “I aspire for my paintings to act as an invitation for contemplation—on the construction and contestation of identity.”

In addition to colonial portraits, Pattni critically examines the legacy of British botanical illustrations. In his pieces, the artist intertwines these illustrations with Mughal florals to form composite flowers, all of which are “intentionally mythological.”

“That impossibility symbolizes the ways colonialism disrupted cultural authenticity, giving rise to hybrid identities that resist neat categorization,” Pattni clarifies. “By reconfiguring both floral languages, I’m crafting a visual metaphor for diasporic identity.”

My Modern Met had the opportunity to converse with Sid Pattni about his artistic practice, the importance of post-colonialism in his work, and the implications of diaspora. Continue reading for our exclusive conversation with the artist.

What initially attracted you to painting as a medium for art?

Painting captivated me as both a material and a conceptual realm. Technically, there is something inherently tactile and immediate about engaging with paint—the layering, the application of color, translucency, and the physical effort of mark-making. Conceptually, however, painting carries a significant historical weight. It has served as both an instrument of empire and a means of resistance.

This tension compelled me—the chance to operate within a medium that historically contributed to orientalist perceptions of India while simultaneously employing it to deconstruct and challenge those narratives.

How has your practice transformed over the years?

My practice has transitioned from being focused on personal narrative to a deeper examination of broader historical contexts. Earlier works explored personal family history and migration more directly, but as time passed, I began to perceive these narratives as situated within larger colonial frameworks that influenced not just my family’s migration but also my comprehension of identity. I’ve shifted toward utilizing existing visual languages—Mughal miniatures, Company paintings, British botanical illustrations—not as static artifacts but as contested spaces of meaning. My current work aims to dismantle and reconfigure these languages to investigate how colonial power continues to influence diasporic identity today.

What initially attracted you to colonial history as an artistic lens?

Colonial history feels close to me—it’s the foundation upon which my identity is built. My family’s migration from India to Kenya and later my own relocation to Australia are all tied to patterns of colonial displacement and global movement. This context prompted me to consider not just personal stories but the structural conditions that generated them.

Visually, I found myself drawn to the way colonial histories have been aesthetically represented: the orientalist perspective in British depictions of India, the cataloguing within botanical illustrations, the simplification of identity in Company paintings. These representations were not neutral—they served as instruments of control. Engaging with colonial history as a framework enables me to critically examine the very images that have defined how Indians—and Indian diasporic individuals like myself—have been perceived and how we have come to view ourselves.

What is the significance of Indian Mughal miniatures to you, and what methods do you employ to reproduce those elements?

Mughal miniatures represent a visual language that is both familiar and foreign to me—a cultural legacy shaped by empire and interpreted through a Western lens.

In my work, Mughal miniatures function as both historical artifacts and sites of disruption. I draw upon their compositional structures, motifs, and viewpoints, often reinterpreting these through paint, textiles, and other media to reflect contemporary diasporic experiences.

What initially motivated you to merge Mughal florals with British botanical illustrations, and how does this act as a form of reclamation?

The floral borders in Mughal paintings symbolized a range of themes